Eight centuries of German and African interactions up until World War I are often glossed over in historical literature. The contributors to Germany and the Black Diaspora: Points of Contact, 1250-1914, published last month, seek to illuminate these intersections and share popular sentiments of the time. Below, co-editor Martin Klimke describes a significant—and still remarkable—relic of this pre-WWI period.

______________________________________________________

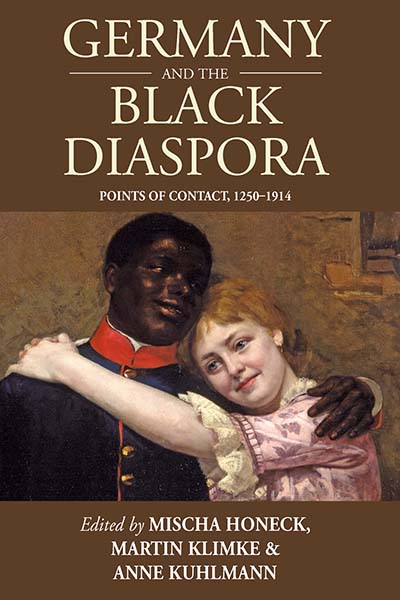

For more than ten years now, visitors to the German Historical Museum in Berlin have paused in amazement before a painting unlike any other in the museum’s collection.

It depicts a man in Prussian military uniform, impeccably dressed, with his arm around a red-haired young woman resting happily in his embrace.

This portrait of two lovers was created by the German artist Emil Doerstling in 1890 during the heyday of the Wilhelminean Empire. In the same year, the recently enthroned Wilhelm II drove Chancellor Otto von Bismarck from office, and the Germans yielded the island colony Zanzibar to the British in exchange for the North Sea island of Helgoland. Much of Germany’s newly gained imperial self-esteem was lodged in the country’s military class, of whom the young officer captured in the painting is a proud representative.

One feature, however, stands out: the man in the picture is black.

His name is Gustav Sabac el Cher. Gustav’s father, August Albrecht Sabac el Cher, was brought to Germany in 1843 by a Prussian nobleman who received August as a “gift” from the Egyptian viceroy Mehmet Ali while traveling the Orient. The Sabacs fared well under the tutelage of the Prussian aristocrat. Gustav was educated by the best teachers, enjoyed close ties to the Hohenzollern court, served in the army, and rose up to the position of imperial bandmaster. Well-respected and fully integrated into German society, Gustav performed in front of kings and emperors. When Gustav Sabac el Cher died forlorn and almost forgotten after the Nazi takeover, Wilhelm II sent a letter of condolence from his Dutch exile.[1]

Gustav Sabac el Cher’s remarkable career is startling because it challenges widespread assumptions about Germany’s historical relationship with people of black African descent. Although Germans joined the scramble for Africa in the late nineteenth century, subjugating and exploiting indigenous populations, the notion of black presences in German social and cultural life—that persons of a darker hue had been actively involved in its making—have been all but expunged from national memory.

Yet the footprints the Sabac family and other black Africans left in the country’s history tell a different story. These footprints bear testimony to myriad black-white encounters in premodern and modern Germany from the Middle Ages to World War I.

These encounters are the subject of this volume.

[1] The story of August and Gustav Sabac el Cher is explored in Gorch Pieken and Cornelia Kruse, Preußisches Liebesglück—Eine deutsche Familie aus Afrika (Berlin: Propyläen, 2007).

_____________________________________________________

Martin Klimke is Associate Professor of History at New York University Abu Dhabi. He is the author of The Other Alliance: Global Protest and Student Unrest in West Germany and the US, 1962-1972 (Princeton University Press, 2010) and coauthor of A Breath of Freedom: The Civil Rights Struggle, African-American GIs, and Germany (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010). He is a co-editor of the Protest, Culture and Society series (Berghahn Books) and of several collected volumes on various aspects of transatlantic and transnational history.

Mischa Honeck is a research fellow at the German Historical Institute in Washington, DC. His first book, We Are the Revolutionists: German-Speaking Immigrants and American Abolitionists after 1848 (University of Georgia Press, 2011), was a Choice Outstanding Academic Title for 2011.

Anne Kuhlmann is a research fellow in Russian history at the Cultural Foundation of the German Federal States in Berlin. In 2010, she received the Sponsorship Award of the Society for Historical Migration Research for her PhD dissertation on black people in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Germany.