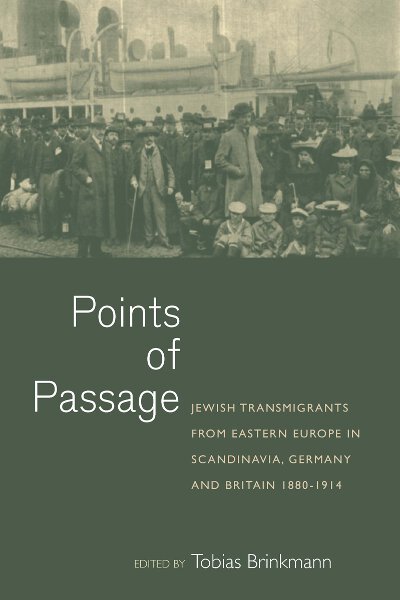

Ellis Island in New York City is a historically recognized entrance point for European migrants to the United States. But if this is so well-known, then why do we know so little about the points of departure? This is one of many research questions that informed the writing of Points of Passage: Jewish Migrants from Eastern Europe in Scandinavia, Germany, and Britain 1880-1914, published last October. Following, an excerpt from the volume — bookended by comments from editor Tobias Brinkmann — delves deeper into these queries.

_________________________________________

When I began researching the history of Jewish migrations in the 1990s I concentrated on immigrants. I collected sources on the settlement of Jewish immigrants from small villages in the Central and Eastern European countryside in Chicago between 1840 and 1900. Within a few years the immigrants built a Jewish community, prospered economically and became respected members of Chicago’s social and political circles. My first book concentrated on two major research questions that continue to drive immigration studies: the impact of forces strengthening or weakening ethnic communities, and the impact of assimilation processes on immigrants.

Studying different aspects of immigration is an obvious choice for migration scholars. Immigrants made (and continue to make) an impact on the economy, society, culture and political system in their host country. They form relationships with members of the native population and other immigrants. Some members of the native population and other immigrants exclude or even discriminate recently arrived immigrants. Data collected by private businesses and state officials, such as the United States Manuscript Census, enable scholars to study the residential and social mobility of immigrants, and processes of adaptation. Researchers of immigration history usually do not have to travel far beyond the location they are studying: most sources are within easy reach, in various local collections and in the respective national archive.

______________________________________________

Few topics in modern Jewish history have been as exhaustively researched as the Jewish mass migration from Eastern Europe to the United States between the early 1880s and mid-1920s. It is indeed difficult to overlook the studies examining the arrival, community building and assimilation of Jewish immigrants, especially in New York, Chicago, and other American cities. Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe transformed Jewish communities around the globe. In Britain, Palestine, South Africa, Argentina, Australia, and many other places Jewish immigrants established new communities or outnumbered older Jewish settlers, often within a few years. In and beyond Eastern Europe the Jewish mass migration was primarily a movement to industrializing cities.

But as I turned my work on Chicago into a book several years ago I realized that several key aspects of the Jewish mass migration remained little understood: Where exactly in Central and Eastern Europe did Jewish immigrants originate, why did they leave their homes, and how did they reach their destination? And how did anti-Jewish persecution in Eastern Europe after 1914 affect Jewish refugees and migrants, especially after the United States and other immigration countries such as Britain began to restrict immigration in the early 1920s? A closer look at the Jewish mass migration between the 1880s and 1920s reveals a number of surprising research gaps. Little is known about the exact causes of the migration, the social history of shetlach experiencing out-migration, and the paths Jewish migrants chose. It is also unclear why and for how long Jews (and other Eastern Europeans) stopped over in transit countries like Imperial Germany and Britain, and how they reached their respective destinations.

Of course, Ellis Island, literally a point of passage into America, situated spectacularly in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty and opposite the skyline of Manhattan, has a much higher symbolic significance than the often inconspicuous departure stations, primitive makeshift facilities for migrant masses at European railway stations, port cities and former control posts along borders that were redrawn several times during the twentieth century. Today, Ellis Island is remembered as America’s iconic gateway. Yet at its dedication in January 1892, the reception center’s main function was to closely screen all arrivals to make sure they did not constitute a threat to American society. The average rejection rate of immigrants arriving at Ellis Island between 1892 and 1914 was low. Only about two percent of migrants were rejected as “undesirables.” Yet a much higher proportion of migrants en route to the United States between 1892 and 1914, among them many Jews, never reached Ellis Island.

This was, in part, due to a sophisticated control system that reached far beyond North America’s shores. Even before 1892, persons who were unlikely to be admitted at an American port of entry, frequently were denied boarding at European and Asian ports – usually by employees of steamship lines, sometimes by American consular personnel, or by state officials in the respective transit countries. The steamship lines faced penalties by the United States immigration commissioner if they transported too many “undesirable” migrants. The steamship lines and the authorities in the transit countries had to cover the costs associated with the involuntary return journey of persons who were not admitted at Ellis Island and similar immigration stations at other American and Canadian ports.

_______________________________

The essays in “Points of Passage” focus on different aspects of the journey of Eastern European Jews (and Christians) to (and from) America. The authors discuss the role of the steamship lines (and the impact of ticket prices), the fate of “undesirable” migrants who were stranded along the journey or refused entry to the United States. The essays show a number of parallels between migrant experiences in the period before 1914 and today. Even when migrants from Eastern Europe faced relatively few restrictions, a not insignificant number were relegated to a legal grey zone, unable to proceed to their destination but also to return to their country of origin.

___________________________________

Tobias Brinkmann is the Malvin and Lea Bank Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and History at Penn State University. His recent publications include Sundays at Sinai: A Jewish Congregation in Chicago (University of Chicago Press, 2012); Migration und Transnationalität: Perspektiven deutsch-jüdischer Geschichte (Schöningh, 2012); and “Why Paul Nathan Attacked Albert Ballin: The Transatlantic Mass Migration and the Privatization of Prussia’s Eastern Border Inspection, 1886–1914,” Central European History (2010).