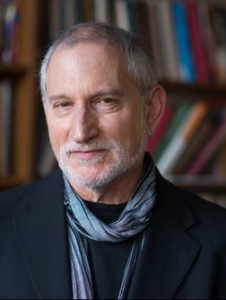

Paul Stoller, whose article “Embodying Knowledge: Finding a Path in the Village of the Sick” appeared in Ways of Knowing, edited by Mark Harris, earned the 2013 Anders Retzius medal for excellence in anthropology—an honor bestowed every three years—April 24. Below, Stoller reflects on his life’s work that helped him earn the award.

__________________________________________

Milestones in life compel you to think about where you’ve been, where you are and where you are going.

In 2012 I received an email, marked as “possible spam,” that invited me to Stockholm in April 2013 to receive the Anders Retzius Gold Medal in Anthropology, which is given once every three years.

When the shock of such an unexpected invitation subsided, I began to think about my life in anthropology. In my years as an anthropologist I long held the assumption, which is perhaps a tad naïve, that anthropologists could transcend the cultural gulf of difference that separates them from their others. I assumed that if you learned to speak the other’s language fluently, your linguistic competence would be a strong indication of deep cultural respect, which could, in time, foster profound understanding and friendship between peoples defined by difference.

That assumption compelled me to deepen my knowledge of the Songhay language. I studied proverbs and learned to talk about little discussed cultural matters—the names of plants, the use of spices in Songhay cooking, expressions associated with farming and healing. The use of these specialized elements of the Songhay language usually impressed my interlocutors, who praised my command of the Songhay language. In markets the anomaly of a white man speaking “old” Songhay attracted crowds of onlookers.

“Where did you learn Songhay?” a few people would ask.

“You speak Songhay better than me,” some would say with not a small degree of exaggeration.

When I “did” the famous market of Ayorou on the banks of the Niger River not far from the border between Niger and Mali, crowds of young people would come to listen me bargain for a beautiful hand-woven Songhay blanket. One day a man from Mehanna, the Songhay town where I conducted my early fieldwork, joined the crowd of Ayoru onlookers.

“Who is this white man who speaks Songhay?” someone asked.

“He’s our white man,” the Mehanna man chimed in.

The long-term relationships I established in the field also reinforced the assumption. I studied with my teacher Adamu Jenitongo for more than 17 years. During that time I felt that we had developed an intimate bond—the loving ties of a father to his son. We had, or so I thought, bridged the wide cultural gulf that had separated us.

In 1988, I mourned his death, which not only brought to an end the life of a wise man, but also changed my life as a field anthropologist. After his death, how could I go on with my work in Niger? Who could replace my mentor? After his death, things soon fell apart, to borrow from Chinua Achebe, for my work in Niger.

Despite my disappointments in Niger, I carried the same assumption with me to New York City. Although I never developed a relationship there that resembled the deep bonds I had shared with Adamu Jenitongo, I still felt that my linguistic and cultural knowledge of things Songhay might enable me to establish friendships that bridged the gulf of social and cultural difference. I liked the fact that in New York City my Nigerien friends called me “brother,” and said that I spoke Songhay like a native. I especially liked it when they bragged about me to their customers.

“He’s lived in my village.”

“He knows our history.”

“He’s a boro hano (a pure/good person).”

When my friends said: “He’s really a Songhay,” I would respond: “Even if a log has been in the river for 100 years, it can never become a crocodile.” I’d follow that proverb, which would invariably provoke much appreciative laughter, with affirmations that I was and would always be an American.

My friends would disagree, which would quietly reaffirm the premise that I was somehow different from other white people. One day in 2004 a phone conversation weakened the foundation of that assumption. I phoned Issifi Mayaki who has been one of my longstanding Nigerien friends in New York. Issifi and I shared a passion for political discussion, but also had enjoyed long and intense debates about religion and culture. We often talked about racism and the general American ignorance about Africa and Africans. He liked to call me his “brother.”

After several rings, Isiifi’s real brother, whom I hadn’t met, picked up the phone.

I introduced myself.

In the background I heard Issifi ask who was on the phone.

His brother said, “Paul.”

“Oh, that’s the white man,” Issifi said, not knowing he had been overheard. Moments later, he picked up the phone and said: “Paul! How are you, my brother?”

For me that incident underscored powerfully that the relationship of non-native anthropologists to their others is vexingly complex. In a short essay in 2005 I wrote about my immediate reaction to the incident, coming to the conclusion that my particular capacities as a fieldworker or as a human being could not alter an always already set of racially-defined sociological boundaries—of pre-colonial and colonial culture—established and solidified years before I had set foot in Niger…How disappointing it is for ethnographers to admit, and in my case it was a grudging admission, that the relationships that they develop in the field, while close, are, in fact, not usually as special as they might think…

One phone conversation did not dispel the feeling that my experiences in the Songhay worlds of sorcery and trade nonetheless had put me in a different category, a category in which a set of common understandings gave me insights into the social realities of my friends. And yet, the applicability of oft-quoted proverb never seemed stronger: “Even if a log floats in the river for 100 years, it can never become a crocodile.”

This clear-sighted set of field expectations didn’t alter the texture of social relations with my Nigerien friends in New York City. We liked one another and we shared much laughter and pleasantry. Our ties continued to be mostly instrumental. They wanted me to buy things from them or send them clients. Sometimes they asked me to write them letters or find them an honest immigration attorney or a first rate French-speaking physician. As any anthropologist doing research, I, of course, wanted to hear their stories so I might try to try to represent their experience in America. In that way I could not only enhance my academic profile, but also help to create the space for an edified conversation about African immigrants in America.

My grudging realizations neither diminished the richness of my ethnographic experiences nor altered the sensuous texture of my ethnographic stories. Although I thoroughly enjoyed my longstanding relationships with my Nigerien friends in New York, I believed that there were distant existential boundaries that we would never cross. In time, as recounted in my forthcoming book, Yaya’s Story: The Quest for Wellbeing in the World, I did cross one of those existential boundaries, which reaffirmed my early assumption that people defined by difference can experience profound mutual understandings.

Read more about Stoller and the Retzius Award at The Huffington Post.

__________________________________________

Paul Stoller is Professor of Anthropology at West Chester University. He has been conducting anthropological research for more than 30 years in West Africa and New York City. The author of 11 books, Stoller’s most recent work is The Power of the Between (2008). In 2002, the American Anthropological Association named him the recipient of the Robert B. Textor Award for Excellence in Anticipatory Anthropology. During the past two years, Stoller has blogged regularly on culture, politics, media and education for The Huffington Post. In April 2013 The Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography awarded him Anders Retzius Gold Medal for his scientific contributions to anthropology. His forthcoming book, Yaya’s Story: The Quest for Wellbeing in the World will appear in 2014.