Nelson Mandela was born on July 18, 1918. Mandela was a South African anti-apartheid revolutionary, politician, and philanthropist, who served as President of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country’s first black head of state and the first elected in a fully representative democratic election. In 1962, he was arrested for conspiring to overthrow the state and sentenced to life imprisonment in the Rivonia Trial. Mandela served 27 years in prison, split between Robben Island, Pollsmoor Prison, and Victor Verster Prison.

This excerpt was adapted from The Decolonial Mandela: Peace, Justice and the Politics of Life by Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni. Chapter 1 of this book is currently available online for free.

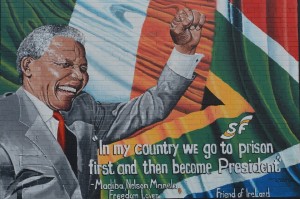

On his release from prison on 11 February 1990, Mandela greeted his supporters in a particularly revealing way, capturing the core aspects of decolonial humanism: “I greet you all in the name of peace, democracy and freedom for all! I stand before you as a humble servant of you, the people”

This statement encapsulated what the philosopher Enrique Dussel termed exercising ‘obedential power’ – command by obeying – founded on principles of politics as ‘vocation’ and an expression of the ‘will to live’ rather than the ‘will to power’. When Mandela presented himself as ‘a humble servant of the people’ he was announcing a new conception of politics in which the exercise of power is not for the self but rather on behalf of the people.

Mandela is one of those politicians that practised politics as vocation – a calling to fulfill a decolonial humanist mission. This explains why Anthony Sampson in Mandela: The Authorized Biography noted that ‘[d]espite Mandela’s political evolution, he still retained his basic African nationalism: his pride in his people and their history, and his determination to regain their rights’.

Mandela can best be described as a radical African nationalistliberal-decolonial humanist who dedicated his life to a struggle against racism, imperialism, colonialism and apartheid. Racism, the slave trade, imperialism, colonialism, apartheid, neo-colonialism and underdevelopment have all existed as the underbelly of Euro-North American-centric modernity since 1492. When Mandela was released from prison in 1990 he knew that his supporters were much too thirsty for peace, democracy, liberation and freedom after enduring over 350 years of multiple forms of oppression. Apartheid colonialism had robbed black people of dignity and humanity itself. Mandela emerges as an uncompromising historian and a champion of decolonial humanism, and his political thought cannot be ignored in the present-day search for decolonial-liberatory modern political theory.

Decolonial humanism is a long-standing struggle for life spearheaded by those the oppressed people exposed to the negative consequences of modernity. These are people who have been pushed by global imperial designs to live in the ‘zone of non-being’. In the ‘zone of non-being’ there is a scarcity of humanism and life itself. Peace, democracy, liberation and freedom, as constituents of life and humanism, are absent in this ‘zone of non-being’. Mandela dedicated his life to the epic African nationalist-humanist decolonial struggle for peace, democracy and freedom. A biographical approach to understand Mandela’s life of struggle with its proclivity towards celebrations and eulogies is inadequate to the task of capturing the various meanings of Mandela.

Decolonial humanism is opposed to the paradigm of war and racism, and is committed to the advancement of the unfinished and ongoing project of decolonization as a precondition for the paradigm of peace and post-racial pluriversal humanism. Therefore, a critical decolonial ethical study of Mandela’s life of struggle and legacy inevitably enables a critical engagement with the broader question of the meaning and essence of being human (subject, subjection, subjectivity, resistance and liberation) and conditions that inhibited the human flourishing, in this case the paradigm of war and apartheid. Decolonial humanism is preoccupied with two fundamental questions that were clearly posed by the leading African philosopher Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze in his book Achieving Our Humanity: The Idea of the Postracial Future.

How would an African or black person anywhere think about the world – the global modern world which thinks of ‘blacks’ as a race – beyond the idea of race but without denying the fact that racial identities and racism are important aspects of the modern experience? In what ways could one transcend the race-conscious traditions of both modern European and African thought which sustain ideologies of race and racism while recognizing that there are in these intellectual traditions powerful tools against racialism and racism?

My book The Decolonial Mandela challenges the paradigm of war as the normal state of human life and Slavoj Zizek’s intervention that Mandela’s iconic status and “universal glory is also a sign that he really didn’t disturb the global order of power.” This is a common critique that cascades from those analysts and thinkers who focus on Mandela the person to the extent of missing the bigger picture of Mandela as an idea, a voice and a representative of a broader decolonial utopic imaginary. This type of critique also minimizes the challenges and sensitivities cascading from global and local circles that needed careful negotiation and navigation before placing South Africa on a new post-apartheid platform of ‘freedom to be free’ as Mandela put it.

There is no doubt that Mandela deployed principles of critical decolonial ethics of liberation to question and challenge the modernity/imperial/colonial/apartheid paradigm of war and racial hatred directly. What is the subject of debate is how successful he was in changing this paradigm. Mandela’s uniqueness lies in his advocacy of a paradigm of peace informed by a full commitment to democracy and human rights, to racial harmony, to racial reconciliation, and to post-racial pluriversalism as part of his contribution to speaking the truth to a Euro-North American-centric world system that continues to be resistant to decolonization, and its shifting global orders that continue to be impervious to deimperialization.

Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni is the Head of Archie Mafeje Research Institute at the University of South Africa. He is the author of The Decolonial Mandela: Peace, Justice and the Politics of Life.

Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni is the Head of Archie Mafeje Research Institute at the University of South Africa. He is the author of The Decolonial Mandela: Peace, Justice and the Politics of Life.