An interview with Jane Murphy Thomas

JANE MURPHY THOMAS is an independent consultant, practitioner, project manager and social anthropologist in projects for UN agencies, NGOs, governments, donor agencies, and consulting firms, specializing in anthropological approaches and community participation in conflict and disaster-prone locations. Her book, Making Things Happen: Community Participation and Disaster Reconstruction in Pakistan was published in July in hardback and Open Access ebook editions. Following the interview are photographs, some never before published, illustrating steps in the reconstruction process.

Can we begin with a quick overview of your work to date and how you came to work in the sphere of disasters and conflicts?

From the time I was a kid in my remote Canadian community, I was a community organizer, facilitator, activist and this continued into adulthood and my first career in the visual arts as an artist and organizer: forming, managing or advising arts organizations, planning events, designing and managing projects, taking on causes and getting participation in all. In the mid-1980’s, when I decided to switch careers to international development I was fortunate to be hired, trained and assigned to co-lead a development education program in Pakistan to look at ‘development’. This brought me into being immersed, living and working with Afghan refugees, who had fled the war next door in Afghanistan, and into their daily lives in refugee camps and enclaves, witnessing the extreme effects of war, the many types of conflict, ethnic and political tensions, the culture and how to function within these complexities.

When that program ended in a year, I then went on for a total of 15 years in different parts of Afghanistan and Pakistan in different communities, sub-conflicts and local disasters, mainly putting my organizing and mobilization skills to use, facilitating the start-up of the first Afghan NGOs, training them to plan and manage relief, reconstruction and development in their own communities. I also lived and worked in Bangladesh for a few years in flood control construction and reconstruction, and the conflict it often causes there especially over land issues. Midway through this time, I also stepped back for a year going to graduate school for the social anthropology of development, later ‘discovering’ disaster anthropology. This was the foundation of experience I brought into PERRP, then living and working for six years in the project areas.

Your book is a detailed discussion of the Pakistan Earthquake Reconstruction and Recovery Project (PERRP). Take us back to the earthquake itself, when and where it struck and the extent of its impact.

At 8:52 AM on October 8, 2005, an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.6 on the Richter scale struck in the high Hindu Kush/Karakorum mountain terrain of northern Pakistan and India with the epicentre being close to the border between the Pakistan’s province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the part of Kashmir administered by Pakistan.

It took the lives of at least 74,000 people, injured an additional 70,000, and destroyed 84% of the houses leaving 2.8 million people without shelter as winter was setting in. Almost all schools, health facilities and public administration buildings were also destroyed.

And when did your participation begin?

In response to the government of Pakistan’s request for help immediately following the quake, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) put out a call for American engineering and construction companies to bid on the USA’s flagship project for this reconstruction, to rebuild some of the schools and health facilities. When USAID issued their ‘Request for Proposals’ to interested companies, the RFP required some kind of community involvement, but it had a highly unusual stipulation. Bidding companies had to include a socio-cultural expert to lead the community participation, and not only that but that this expert had to be part of the senior management team. Normally, if included at all, people’s participation is considered a separate duty, often outsourced to NGOs, and is treated as incidental and not integral to the reconstruction, seriously weakening the participation, hence effectiveness of it. Later interviewed, USAID personnel responsible for this stipulation explained how they had learned that construction frequently fails when local people are not involved and in this project, they wanted it integrated from the top.

One of the bidding companies found me through a CV data bank and had me help them write this part of their proposal. They won the bid and I went to work on the project from day one in the senior management team, along with engineers and construction planners as the sociocultural expert. Starting together, at the same time helped emphasize that both the technical and sociocultural ‘sides’ were responsible for the success of the project. I then recruited, hired and trained eleven local people to act as the project’s social mobilizers in a sociocultural team. We started the participatory process by carrying out a needs assessment with stakeholder groups: government, community leaders, construction contractors and the project’s own highly experienced engineer/construction managers to identify in construction ‘what could go wrong’ or what ARE the most common problems in construction that involve local people? For each answer, we asked so what needs to be done about each point, how to prevent or manage it? Then we turned this into agreements and the integrated technical and social step-by-step process before, during and after construction.

The focus of your book is sociocultural side of post-disaster infrastructure reconstruction and the necessity of effective interactions between construction and local people. How did PERPP go about handling this community participation?

By the time PERRP project arrived to start work, a year had passed since the quake (time for the bidding process to be completed). In this time many dozens of local and international NGOs, UN agencies and other organizations had already started hundreds of projects to reconstruct buildings, but many were already in trouble, with construction stalled or even abandoned. The main reasons for this were land issues, conflict amongst people over land and other matters, and lack of available, effective, representative community-based groups. Those projects relied on local government or powerful people to solve these problems but were unsuccessful. Clear to me, some of the solutions had to come from the grass roots but local people were rarely consulted.

As is far too common in disaster assistance, affected people had been treated as helpless victims and no expectations were put on them to help prevent or solve the problems. Having worked in the region for several years on the ground in relatively similar rural, conservative cultures and communities, I knew that communities have strengths, resources, capabilities and ideas that were going untapped, and decided this was the best time to tap those, resulting in PERRP taking a partnership/shared responsibility approach. To do this, the sociocultural program had to ensure the project would be culturally and conflict-sensitive, support the construction while increasing community capacities even more.

Once assessments identified it was technically and socially feasible for this project to construct a new place in a certain location, a public process was established where communities were offered a partnership. The project would design and build a new school or health facility, if the community agreed to a long list of conditions, first that the community needed to form a representative group. This committee’s main role was to handle any conflict that might arise that could interfere with construction. Their next duty was to take part in a process to settle all the related land issues before design and construction would start.

We see some of your photographs below, showing some fine new buildings. It looks like a success story. What in particular worked so well?

I’d have to say it was the planning, heavy monitoring, agreements and co-ordination set up among the project engineers, design and construction contractors, social team and community members.

The company that won the bid – CDM Smith – is a major international firm and its contract with USAID was to hire and supervise Pakistani companies to design and build the new places. To do so, besides independent external monitoring, the project had its own internal monitoring structure, with Pakistani engineers, including one full time project engineer at each construction site to monitor the local contractor doing the construction, then three more levels of monitors who frequently visited the sites to oversee and check on various aspects. Each location was under strict building standards to be seismically sound and under a tight time schedule. It also helped that communities made input to the design helping to avoid some costly mistakes and shared responsibility to keep construction on schedule by preventing the all too common conflicts.

The overall work was enhanced by social mobilizers and engineers being trained together on the project process, and by being matched as counterparts at each construction site. This meant they, along with communities and construction contractors were jointly responsible to adhere to agreements made: land issue settlement, the Committee-Contractor agreements, communication protocols, code of conduct, the step-by-step social and technical process from start to end. While much of the other reconstruction was never started, was stalled or abandoned even for years, PERRP’s experience was completely different: the project built its assigned 77 large high schools and health facilities and all but two were completed on schedule or ahead of it. Out of PERRP’s 50,000 construction days only 8 were lost due to conflict. This success was due to the strong construction management, along with the people’s participation and cooperation.

Overall, do you think the community was satisfied with the process and its outcomes?

Community members saw being asked to participate as a welcome form of recognition and they responded with enthusiasm. The most commonly repeated remark in communities by elders, health workers, teachers, students, parents, prominent people and others was ‘when you first came here and started to talk about us participating, we didn’t know what you meant, but now we know and we really like to participate like this. We wish others would ask us too’. There was a clear sense of ownership on the project, pride in helping in any way, even competing with each other to do so, and countless examples of communities taking their own related initiatives (an overworked word but entirely real sign of ‘empowerment’).

Capacities built included self-confidence, community organizing, some new conflict management applications, raised expectations for construction management and transparency in general, monitoring and evaluation and so on. The committees, however, did not continue after the project, mainly due the re-emergence of the old power structures. Even so, those capacities are undoubtedly being put to use in other endeavours.

There must have been particular challenges or obstacles too: what sort of things didn’t go so well or proved contentious to the community?

Conflict was the main risk. This is a conflictual part of the world, with Afghanistan close by on the west side, and the India-Pakistan conflict over Kashmir, where most of the project was located in the part of Kashmir administered by Pakistan. Communities themselves were divided along religious, ethnic, caste and political alliance lines, and separated into layers power. The social team led in dealing with the power structure, keeping the project conflict-sensitive and to do no harm; preventing conflict or managing it if it still happened.

At first, some local powerful people did not want community participation. They attempted to prevent it by saying, ‘no need, I can tell you everything you need to know or do whatever you need to do. Nobody else needs to be involved’. We addressed these situations by explaining that the donor required PERRP to include community participation and it was

one of the conditions of doing construction. Such elites relented when PERRP also pointed out the challenges and quantity of work needed (especially to settle land issues, prevent conflict, etc.), and how these issues would be far better handled by community members sharing responsibility.

A few of the project engineer/construction managers also did not want a social program in the project. They had never worked with social mobilizers before and didn’t want them or community people involved. They were highly experienced in construction management and up to now on other construction jobs they had either ignored or dismissed issues in the community and thought that involving local people was unnecessary and would just distract them from the ‘real work’, while even admitting this frequently resulted in stalled or abandoned construction.

Soon, however, those attitudes changed, when for the first time they witnessed social mobilizers working with the people, often in highly complex situations, getting their views and cooperation and solving problems. Within the first year, the engineers and social mobilizers were working closely together.

The ‘what could go wrong analysis’ at the beginning of the project helped foresee the range of problems, including those subjects that could be obstacles or contentious in the communities, such as powerful people wanting to keep control; the cultural norms for purdah or separation of the sexes and the multilingual nature of the project area. The social process was designed to address these factors.

Do you think that all the techniques employed are basically translatable to other communities around the world?

Yes, for sure, without any doubt. Why? The techniques or approaches already come from elsewhere! In PERRP, we did not invent these participatory/do no harm/conflict prevention and resolution techniques, attitudes or approaches. All we did was adopt or adapt the ideas of main historical thinkers such as Paulo Freire, Robert Chambers, Mary B. Anderson and borrowed ideas from various conflict-sensitive, participatory movements put into practice by some NGOs in many countries (even other parts of Pakistan) in other sectors such as agriculture, forestry, health, education, water and sanitation and livelihoods.

The only difference in PERRP was that we applied them to disaster reconstruction. Somehow the attitude has evolved in emergency agencies that disaster victims only need handouts. To save lives, it is true that physical help in the earliest stages is necessary, but even then or soon, there are other local people who can play leading roles, as shown in PERRP.

Now that the book is out, who do you hope will benefit from it most?

It’s a wide potential audience, such as people and organizations involved in relief; development; disasters; cultural analysis and applied anthropology; building design, project design and management in construction or reconstruction; peace and conflict management; people’s participation and community development, and international aid. This includes practitioners, academics, researchers, students, community leaders, decision-makers in governments, institutions, NGOs, and business sectors.

And it’s Open Access too, so this was clearly an important option for you?

With the book now Open Access people anywhere in the world can get immediate, free access to it. This could encourage much wider discussion and reflection on the sociocultural side of construction or disaster reconstruction, at the same time give ideas for how technical and sociocultural specialists can work together for best results. As disasters are increasing in number and severity around the world, the need for reconstruction grows accordingly. The idea of this book, then, is to help be better prepared for these future reconstruction projects.

Engaging with communities

Much of this project’s reconstruction was at high altitudes, near the Line of Control between Pakistan and India. This was a typical introductory community meeting to discuss reconstruction of a health facility here and the community’s participation in the project. Photo Ghayour Abbas.

Social mobilizers (front left) from the project’s sociocultural team, met frequently with committees formed to participate in the project, to give input, help plan, prevent or solve problems.

Amid the rubble and temporary structures, project architects met with community members to get input for the new school or health facility design.

The project facilitated to have land issues settled before construction started. Here, with school construction underway, measurements were taken again to verify a boundary line.

Construction begins!

When construction was ready to start, communities organized celebration events such as this one at Government Girls’ High School in Azad Jammu and Kashmir. Photo Zia Ahmed.

The results

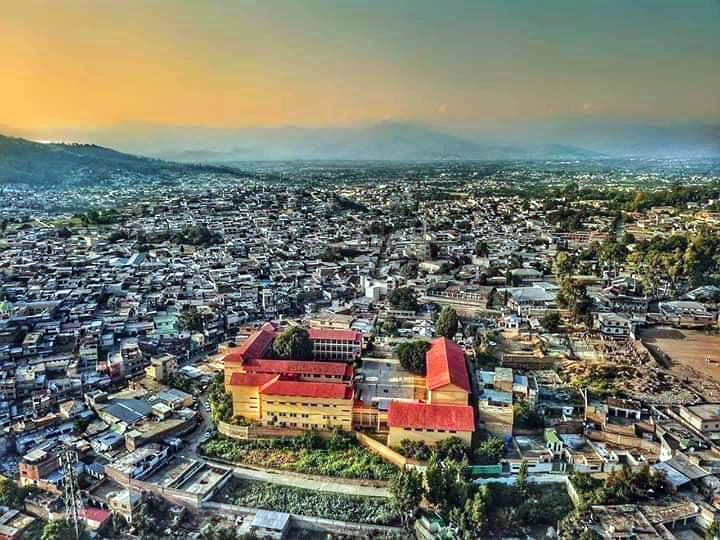

Most facilities in PERRP were built in remote rural areas, but this one was in a densely populated city and was the project’s largest at 84,000 square feet. Government Boys’ Higher Secondary School Manshera #1.

Students and teachers pose outside their newly constructed school, designed in a wedge shape to fit the challenging site.

In these remote locations, there are no libraries even in the schools and students rarely see books outside their own text books. Here the author sat with students to show them other colourful books in the Urdu language.

With the new construction, PERRP introduced the ‘Library Challenge’ for communities to start their own first school libraries, holding the first book fairs (pictured) for teachers, parents, students and public to buy their library books from Pakistani publishers.

If you want to know more about our books please sign up for email newsletters in the subjects of your choice. Or just email us, we’re always happy to help!