Love-locking, the attachment of a padlock to a public structure, is the forte of the traveler. Although not exclusively a tourist custom, it is a popular practice for people visiting a new place and wanting to leave their mark on it. The love-lock has become the inverted souvenir: left behind rather than taken away, but still a token of experience. And social media brims with photographs and videos of tourists locking their love on bridges and monuments – photos and videos that become the modern-day postcard, conveyed to family and friends back home.

Throughout the 2010s, global travel meant millions of love-locks were being locked at popular tourist sites around the world. This was often in defiance of local authorities’ wishes, such as on the bridges of Paris, Rome, Prague, and New York. Labelling love-locking a punishable act of vandalism didn’t stop the custom, which was growing exponentially, appearing on all continents bar Antarctica. It became one of the fastest growing global folk customs in history.

And then 2020 happened. Like so many things, travel was stymied by the Covid-19 pandemic. Planes were grounded, airports open only to essential international travel, and local roving became restricted. Many popular destinations closed, along with much of the hospitality industry, and tourists became a rare breed. So, what happens to a tourist custom when there are no tourists?

Sadly, I’ve been unable to conduct fieldwork that would answer this question. A folklorist is subject to the same rules as everyone else, and so nearly nine months of local lockdown (I live in Greater Manchester, UK) has prevented me from travelling to any popular love-lock sites. However, I have gained a few insights into how the custom has adapted.

A small footbridge in my local park has, for as long as I’ve been traversing it, never accommodated any love-locks. During the pandemic, two locks appeared. Two is hardly a mind-blowing figure, but it could be significant that the custom only emerged in my corner of the world during a national lockdown. Especially when we consider what has been observed elsewhere in the country.

Ethan Doyle White, interdisciplinary scholar of religion and magic, has observed a marked increase in love-locks in his home city of London during the pandemic – despite the decrease in tourism. Writing for the Folklore Society’s newsletter (FLS News 92, November 2020, pp.6-7), Doyle White remarked that, ‘Some do not appear to reflect the conventional idea of the love-lock as a romantic commitment’, but rather celebrate or commemorate familial bonds. Has love-locking therefore become a more localized custom, not only practiced at home, but also in celebration and commemoration of home?

Other love-locks have been spotted across the UK bearing messages of thanks to the national health service (NHS) or images of rainbows, a symbol nationally adopted to represent both hope and the NHS during the pandemic. This is in keeping with the many assemblages formed during lockdown, from snakes of painted pebbles to assemblies of pandemic scarecrows. Some convey gratitude to the NHS; others are expressions of communal solidarity and support. Through these growing assemblages, local residents communicate with each other, and with each deposit representing a community member or household, they can come together safely, even if only in metaphor. In such instances, love-locks aren’t a traveller’s mark left in a new place, or even a couple’s declaration of romantic love to each other. Instead, they are a community’s declaration of fellowship and hope.

Ceri Houlbrook attained her doctorate in Archaeology from the University of Manchester, and is a lecturer in Folklore and History at the University of Hertfordshire. Her primary research interests are contemporary folklore and the material culture of popular customs and beliefs. She has published previously on the British phenomenon of coin-trees and the history and folklore of concealed objects.

About the book

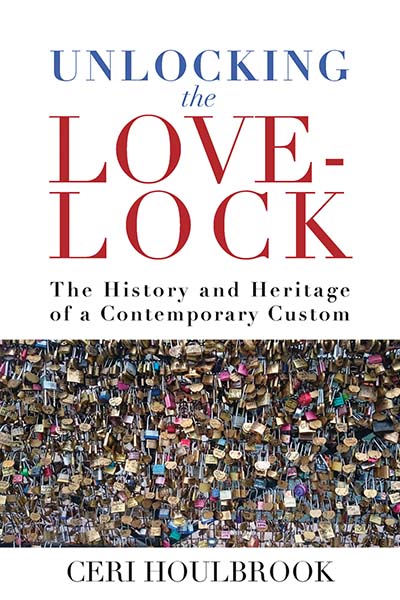

A padlock is a mundane object, designed to fulfil a specific – and secular – purpose. A contemporary custom has given padlocks new significance. This custom is ‘love-locking’, where padlocks are engraved with names and attached to bridges in declaration of romantic commitment. This custom became popular in the 2000s, and its dissemination was rapid, geographically unbound, and highly divisive, with love-locks emerging in locations as diverse as Paris and Taiwan; New York and Seoul; Melbourne and Moscow. This book explores the worldwide popularity of the love-lock as a ritual token of love and commitment by considering its history, symbolism, and heritage.

Don’t miss out on new title announcements or special offers related to your areas of study. Join our mailing list to receive updates on the subjects of your choice.