by Rachel Douglas-Jones and Justin Shaffner, editors of Hope and Insufficiency: Capacity Building in Ethnographic Comparison

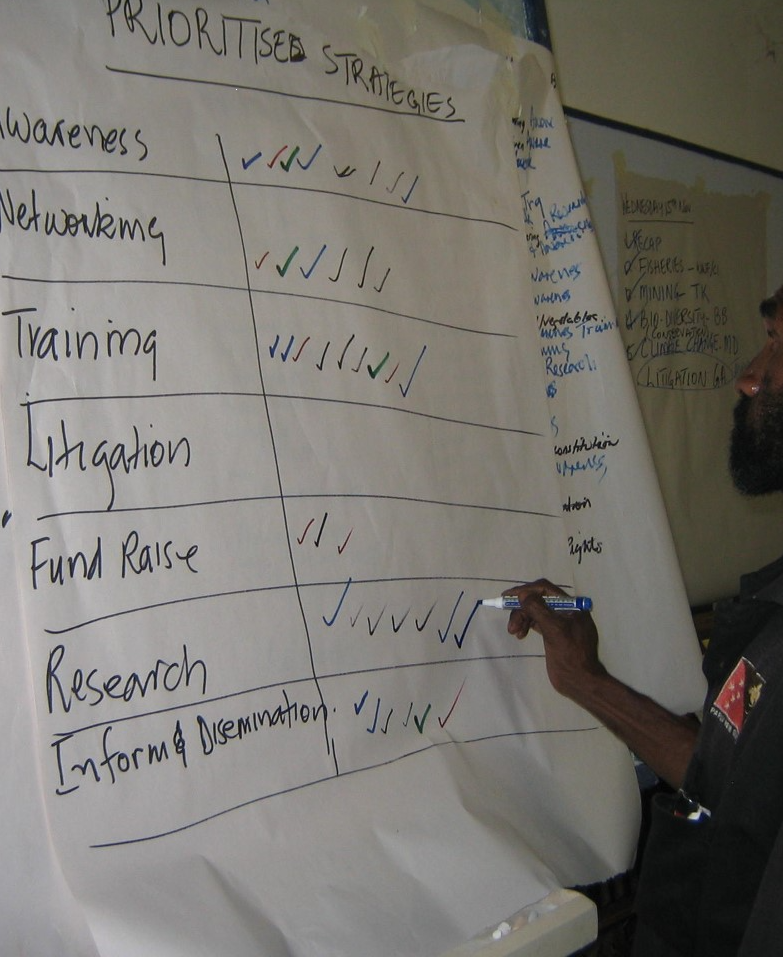

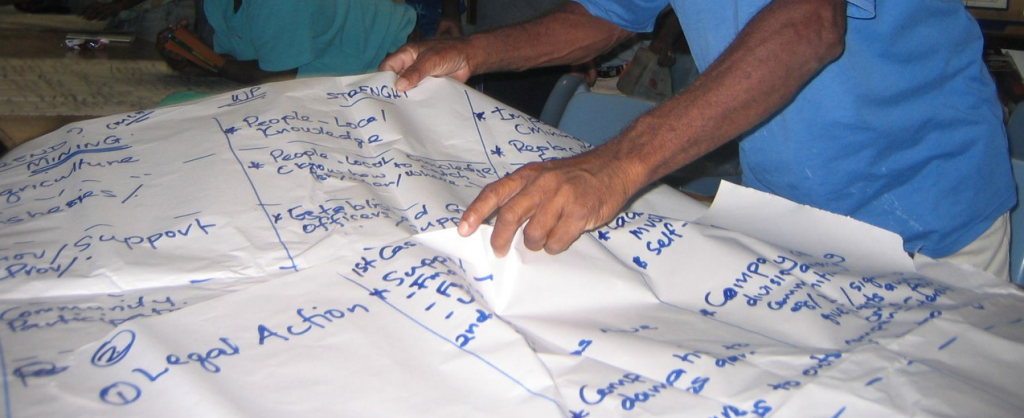

We open our new edited collection Hope and Insufficiency by traveling the world in workshops. Three capacity building events, ranging from Paramaribo to Addis Ababa, sketched as thumbnails, form our introductory paragraph. These three events, drawn from thousands, simply demonstrate the breadth of topics to which it is applied. Capacity building, or its more recent iteration as capacity development, is, we argue, both ubiquitous and under-theorised within the social sciences. The title of our book identifies characteristics of capacity building’s intervention: as we put it, hope and insufficiency interplay in a way that makes the idea of capacity building persuasive.

Origins

While the book sets up a series of examples that bring capacity building into ethnographic focus, it has its origins in the doctoral fieldwork of the editors. When we both encountered capacity building organisations during our research, we each sought out literature to answer the questions that arose: How had anthropologists previously engaged with capacity building projects during fieldwork? How to describe the roles and position of those set up to have their ‘capacities’ built?

Our questions about what was imagined to constitute capacity, and the mechanisms by which it was thought to be built, led us to convene a panel of colleagues who could also speak to the question of capacity building through ethnography. With a follow up workshop, supported by the Wenner Gren foundation in Copenhagen in 2015, we were able to develop the chapters found in this collection.

Questions

The book exists as a resource for understanding what capacity building looks like today. Each chapter addresses a distinct encounter with capacity building, and each presents a variation on what ethnographic attention does for critical analysis. Together, these chapters support students and scholars in their own research by exploring three areas.

First, what does capacity building look like? Who is involved? How does it gain traction and translate into activities, events and policies? Answers to these questions help us consider options for theorising capacity building as policy itself in practice.

Second, who gets to define capacities? Closely related is the question of where capacity is thought to inhere: in what or in whom? And crucially for any ethnographer, how do these claims gain legitimacy? What material and social technologies ground them?

Third, what strategies are available to analytically address the way those who use capacity building conceptualise and enact change? Our interest in the hope of ‘capacity building’ lies in its ties to promised futures and the transformations that will (may) ferry participants there. This requires attending to how possibilities and potentials are invoked and mobilised in the pursuit of other ways of doing or being. As several of the chapters demonstrate, the implication of capacity building in mechanisms of measurement means that the transformation it seeks is often comparative, generating (measurable) insufficiencies to make absences into potentials.

In the Classroom

For lecturers and professors, a classroom exercise is a great way into the worlds these chapters describe. Ask students to search in pairs for instances of capacity building that have taken place in the last month. They can search your or their local area, state, a country the course has recently discussed. When they find their examples – and they will find them – ask each to present on what they can glean of who is building whose capacity, and to what ends. In this way, the various uses of the word, and practices it covers, will become rapidly apparent.

Reading across the chapters of this collection opens up what capacities, human or otherwise, are thought to be. By not taking capacity building’s promises for granted, the chapters both advance our understanding of capacity building’s ubiquity and develop anthropological purchase on its persuasive power.

Learn more about the book here.

Rachel Douglas-Jones is Associate Professor at the IT University of Copenhagen, where she is currently the PI of Moving Data- Moving People, a study of emergent social credit systems in China through the lens of trust. Her recent publications include ‘Committee as Witness’ (The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, 2021) and she is the editor (with Antonia Walford and Nick Seaver) of Towards an Anthropology of Data (JRAI, 2021)

Justin Shaffner is a Research Associate at the Center for Social Solutions at the University of Michigan where he focuses on issues related to the “future of work” and global commodity chains. He is editor (with Huon Wardle) of Cosmopolitics: The Collective Papers of the Open Anthropology Cooperative, Volume 1 (OAC Press, 2017); and co-founder of Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory.