The New York Times recently featured an article on the Wannsee Conference, one of the most significant events in the history of The Holocaust. On 20 January 1942, fifteen senior German government officials attended a short meeting in Berlin to discuss the deportation and murder of the Jews of Nazi-occupied Europe. Despite lasting less than two hours, the Wannsee Conference is today understood as a signal episode in the history of the Holocaust, exemplifying the labor division and bureaucratization that made the “Final Solution” possible. Yet while the conference itself has been exhaustively researched, many of its attendees remain relatively obscure. In recognition of the historical 80th anniversary this year, we present an excerpt from The Participants: The Men of the Wannsee Conference (edited by Hans-Christian Jasch and Christoph Kreutzmüller). We are also offering 25% off the paperback for this title until 5th February, 2022. Just use code JASCH6713 at checkout.

On 20 January 1942 senior German officials came together for a meeting, to be followed by breakfast, in a grand villa overlooking Lake Wannsee to discuss the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” in Europe. What sort of men were they? This is what most visitors to the House of the Wannsee Conference Memorial and Educational Site ask themselves when they visit the former dining room where the meeting very likely took place.

….

Who were the conference participants? We must start by stating the obvious: there were no women among them. Given the extreme chauvinism of the Nazis, who tolerated women in leading positions at best in the caring professions, this fact is hardly surprising. Notwithstanding the 2001 TV film Conspiracy, and specifically Kenneth Branagh’s Heydrich, who seems to have stepped out of a Shakespeare play, these men do not at first glance appear to be evil psychopaths. As shocking as it seems, they were “ordinary men” (Christopher Browning) who knew how to behave, who could appreciate fine architecture (with a view of the lake) and the good things in life, including the refreshments, possibly looted from across Europe, provided after the meeting. The participants at the conference did not make up an established group. The group was convened only for this particular meeting and represented a cross section of the Nazi elite. This illustrates how a “modern division of labor,” as Gerald D. Feldman and Wolfgang Seibel observed, was an important premise for the mass murder of European Jews. If nothing else, it allowed the perpetrators to think that they were only one link in a chain of command and therefore not individually responsible for their deeds.

Despite their high ranks, the men profiled in this volume had an average age of little over forty-two, making them relatively young. With the exception of Martin Luther and Wilhelm Stuckart, they came from middle-class families. They were the sons of civil engineers, bakers, farmers and manufacturers. One of them (Friedrich Wilhelm Kritzinger) was the son of a pastor. Eleven of them had Protestant backgrounds. Three were Catholic. Otto Hofmann described himself merely as “a believer” (“gottgläubig”) but most probably also came from a Catholic background. The majority of the participants were in SS-terminology Prussians, but Rudolf Lange and Eberhardt Schöngarth came from Saxony, Josef Bühler from Württemberg, Heinrich Müller from Bavaria and Otto Hofmann from Austria, while Georg Leibbrandt was a Russian-German born near Odessa.

Seven of them—Roland Freisler, Hofmann, Kritzinger, Alfred Meyer, Müller, Erich Neumann and Luther—had fought in the First World War and saw themselves as survivors of what Ernst Jünger termed the “Storm of Steel.” Only one of them (Müller, who did not graduate from high school) failed to reach the rank of lieutenant. Neumann was badly injured in the White Men’s Great War (Arnold Zweig), while quite a few (Freisler, Hofmann, Kritzinger and Meyer) had been prisoners of war. The other eight participants belonged to the so-called “war youth generation”—as described by Ernst Gläser in his excellent novel Born in 1902, which was burnt on 10 May 1933 by students on what is now Bebelplatz in Berlin—dubbed the “uncompromising generation” by Michael Wildt. It was shaped by the fervent patriotism and hardship of the war years, as well as by the chaos of the revolution in 1918/19, the brutal Silesian Uprisings, the occupation of the area west of the Rhine and the Ruhr region by French and Belgian troops, and hyperinflation. There is no doubt that these turbulent years had a formative effect. Ultimately, they wanted to win the war their fathers had lost, and to prove their mettle.

Ten of the fifteen participants had been to university. Eight of them had even been awarded doctorates, although it should be pointed out that it was considerably easier to gain a doctorate in law or philosophy in the 1920s than it is today. Eight of them had studied law, which, then as now, was not uncommon in the top positions of public administration. Many first turned to radical politics as members of Freikorps or student fraternities. Three of the participants (Freisler, Klopfer and Lange) had studied in Jena. In the 1920s, the University of Jena was a fertile breeding ground for nationalist thinking. With dedicated Nazi, race researcher and later SS-Hauptsturmbannführer Karl Astel as rector, it developed into a model Nazi university. Race researcher Hans Günther also taught there. Others, such as Reinhard Heydrich, joined the SS because they had failed to launch careers elsewhere, and only became radical once they were members of the self-acclaimed Nazi elite order.

Some participants, chief among them Freisler, Hofmann, Meyer and Stuckart, were alte Kämpfer—that is, “old fighters” who had joined the Nazi Party in the 1920s and were therefore permitted to wear the Golden Party Badge. As a Gauleiter (regional head of the Nazi Party), Meyer occupied an especially high position in the Party hierarchy, which is why he appears at the top of the Protocol’s list of participants. While Adolf Eichmann, Heydrich and Luther joined the Party in 1931/32, when it performed well in elections, others such as Bühler, Klopfer, Neumann, Leibbrandt and Schöngarth were what was called “the fallen of March” or “Mayflies,” one of the hundred thousands who only joined the Party for opportunistic reasons once its power had been consolidated. Lange, Müller and Kritzinger were only admitted to the Party after the ban on membership was lifted in 1937. The representatives of the Reich Main Security Office and Hofmann, head of the SS Race and Settlement Main Office, were senior figures in the SS. Klopfer, Stuckart and Neumann had long been members of the SS. Ten days after the conference—on the ninth anniversary of the so-called Machtergreifung (seizure of power)—Stuckart was made a SS-Gruppenführer and Klopfer a Brigadenführer. Both thereby attained the rank of general.

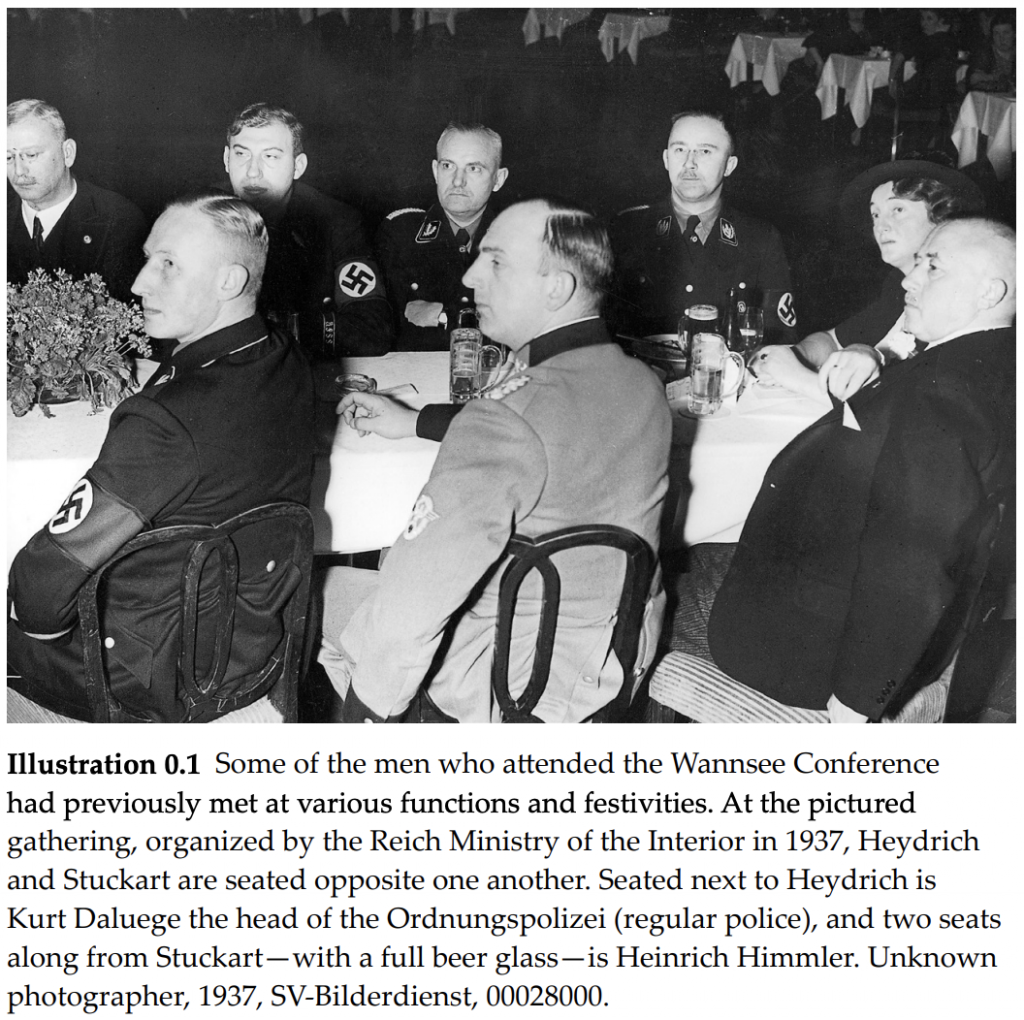

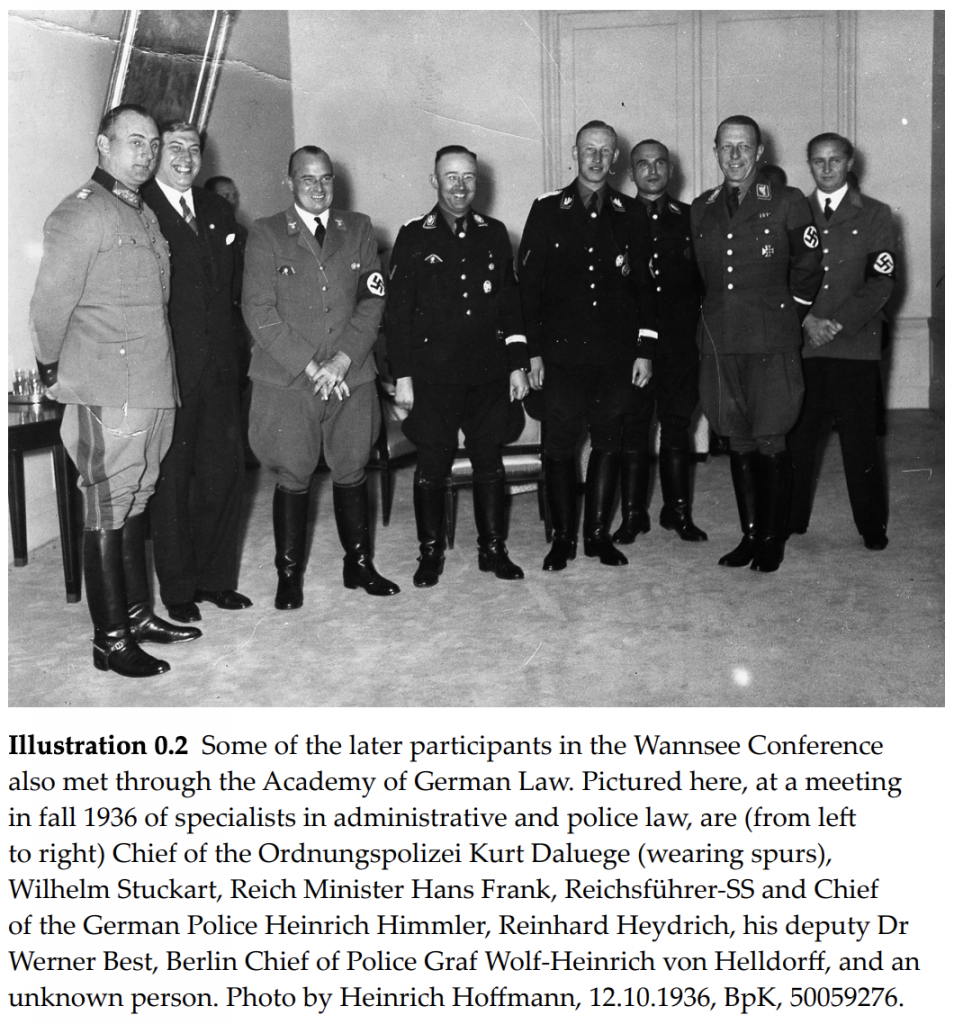

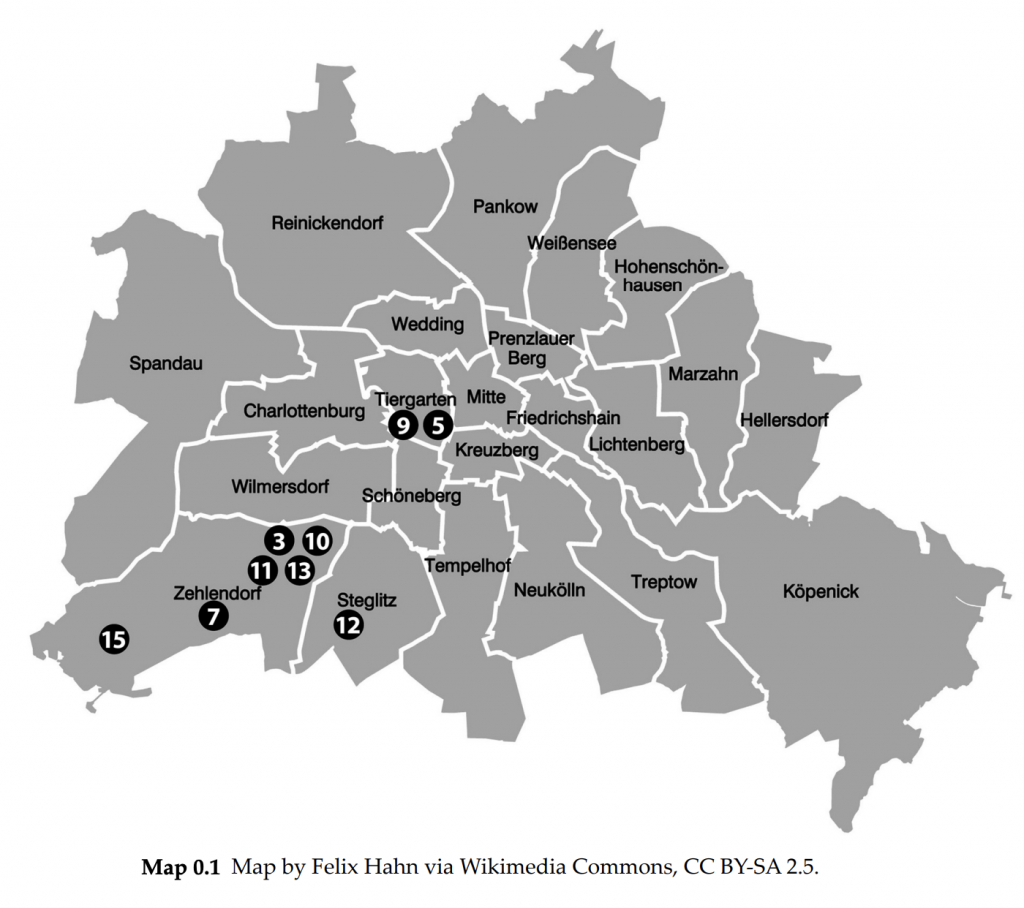

The study of these men’s biographies provides clear evidence that the participants had met one another well before the conference on 20 January 1942: almost all of them lived in Berlin’s affluent south-west or in the fashionable Tiergarten district, and some of them were members of a men’s club where many Nazis networked, including many senior officials on Wilhelmstraße. Freisler, Heydrich and Stuckart, as well as Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger, the Higher SS and Police Leader of the General Government, who had also been invited to the conference, belonged to the German Aero Club, under the patronage of Göring. Freisler, Meyer and Heydrich were members of the Reichstag, where Kritzinger sat on the government bench. Freisler, Kritzinger, Neumann and Stuckart knew one another from the Prussian State Council and the Ministerial Council for Defense of the Reich. Bühler, Freisler and Stuckart would have encountered one another in the Academy for German Law.

Eichmann, Heydrich, Müller, Neumann and Stuckart all attended the high-level meeting held on 12 November 1938 in the Ministry of Aviation, when Göring communicated Hitler’s order that “the Jewish Question be now, once and for all, summed up and resolved one way or another.” In the course of the four-hour meeting, Heydrich proposed a central office for Jewish emigration, similar to that in Vienna, in order to further expedite the emigration of Jews—which was increasingly becoming more of a desperate flight in the wake of the pogrom still often referred to as Crystal Night. The proposal met with Göring’s approval. In January 1939 he established the Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration within the Interior Ministry and made Heydrich its head. When Heydrich issued his invitations to the Wannsee Conference, he enclosed a certificate of appointment signed on 31 July 1941 by Göring, naming him the coordinator of the “definitive resolution of the Jewish Question in the German sphere of influence in Europe.” This explicitly extended the powers granted to Heydrich with the founding of the Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration and thus made implicit reference to the conference held on 12 November 1938. In this respect, the pogrom of November 1938 and Göring’s conference were directly linked to the Wannsee Conference.

By this time, the “Resolution of the Jewish Question” was being debated in various public media with astonishing openness. AntiJewish propaganda was stepped up in the wake of the invasion of the Soviet Union in summer 1941 and the first systematic deportations of Jews throughout the Reich in October 1941. The German media by and large adhered to the instruction issued by Reich Press Chief Otto Dietrich in the Daily Watchword (Tagesparole) on 26 October 1941 to bear in mind Hitler’s “prediction” made on 30 January 1939. “Long before the outbreak of the current war,” he wrote, Hitler had “specifically warned international Jewry against starting a war against Nazi Germany.” But this, Dietrich continued, is what they did and, just as the Führer predicted, “the Jews are paying for the blood guilt they brought upon themselves by their own crimes. The Jews alone have this war on their conscience. This issue must be addressed in two columns

on the front page.”

On 16 November 1941 the highest circulation weekly newspaper Das Reich carried a lead article headlined “It is the Fault of the Jews!” by Joseph Goebbels, Reich Minister for Propaganda and Gauleiter of Berlin, whose state secretary Leopold Gutterer was also one of the original invitees to the Wannsee Conference:

“We are now seeing the fulfillment of this prophecy, and the Jews are suffering a fate that, albeit hard, they have more than deserved. Compassion or even regret are totally inappropriate. World Jewry has completely underestimated the strength of its own power in its instigation of this war, and is now gradually experiencing a process of destruction which it wanted for us and would have mercilessly imposed on us if it had had enough power. Now the situation we are in is, according to the Jews’ own law, an eye for an eye.”

The launch of the Soviet counteroffensive, Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and Germany’s declaration of war against the United States turned the war into a world war. Around this time, Goebbels referred in his diary to a meeting on the afternoon of 12 December 1941 between Hitler and the Nazi Reichsleiter and Gauleiter, including Meyer, in his private rooms at the Reich Chancellery:

“With respect of the Jewish Question, the Führer has decided to make a clean sweep. He prophesied to the Jews that if they brought another world war to pass they would experience their own annihilation. That was not just an empty phrase. The world war is here, and the annihilation of the Jews must be the necessary consequence. The question has to be examined without any sentimentality. We are not here to pity Jews, but to have pity for our own German people. If the German people have sacrificed about 160,000 dead in the battles in the east, the instigators of this bloody conflict will have to pay for it with their lives.”

The publication Deutsches Recht, which was compulsory reading for many Nazi lawyers, also referred to the solution of the “Jewish Question” “without sentimentality.” Jewry was “bound to suffer historical and earthly death . . . as far as the historical phenomenon of Jews in Europe is concerned.”

Owing to a lack of historical evidence, we know little of the participants’ activities immediately prior to and after the meeting on 20 January 1942—a cold, clear Tuesday in the middle of an unusually long period of frost. Most of them would have read the newspapers’ coverage of the fighting in- and outside Europe. That day, a front page article headlined “Japanese Troops on the Southern Tip of Malacca [Malaysia]” in the Berlin edition of the Nazis’ official newspaper Völkischer Beobachter reported that the town of Feodosia in Crimea had been “recaptured” but that the Red Army—described as “Bolshevists”—was attacking on the Donetsk front with “strong forces.” A propaganda unit report on one infantry unit’s defensive battle hinted that the Wehrmacht was struggling with inadequate equipment and suffering heavy losses. The article described a speech made by the U.S. president, in which he announced a drastic boost in U.S. war production, as a “bluff.” The Berlin Nazi paper Der Angriff carried the headline “Germans and Romanians Recapture Feodosia in Bold Attack” and further reported on the successes of the Japanese army in Malaysia. In another article, headlined “Unwavering Defiance,” Robert Ley, head of the German Labor Front, maintained that soldiers in the grip of “honest fanaticism” were invincible. But his words—“German men, German women. German workers, citizens and farmers. Only unwavering defiance will ensure victory . . . now more than ever. We will never capitulate!”— indirectly conveyed just how difficult the situation—known as the “winter crisis”—had become.

On the last page of Der Angriff, alongside an advertisement for Togal pain relief pills, a newspaper entitled “Global Battle: Quarterly Journal on the Jewish Question” was touted as the “leading publication in the field of the Jewish problem.” Published on the day of the conference—“The Jewish Question in politics, law, culture and the economy”—opened with the typical conspiracy theory that the Jews were to blame for the United States entering the war and were ruining the U.S. national budget. In the reviews section of the journal, published by an Institute for Jewish Question Studies, the fourth edition of a paper on “The Jewish Question: Material and How to Treat it in School” was positively received, although the reviewer felt that “the part on method should be extended if a further edition is published.” In a special supplement, not intended for general publication, the reader’s attention was drawn to an order banning Jews wearing the yellow star from using public telephone booths.

The conference participants presumably knew about this ban already. Having read the newspapers, most of them had probably worked for some hours before driving straight from their offices around Wilhelmstraße to Wannsee. Some of them traveled together, to save on gasoline and discuss the meeting ahead. We know that Klopfer, for instance, drove to Wannsee with Kritzinger. Almost certainly Meyer and his subordinate Leibbrandt would have arrived together, too. It is likely that the staff of the Reich Main Security Office who had traveled from farther afield—Schöngarth and possibly also Lange—stayed in their employers’ guest accommodation in the villa, which was fitted with furniture stolen from Jewish homes in Prague, and advertised in a Security Police newsletter as offering “all creature comforts.” They would have needed only to descend the stairs from the guest rooms on the first or second floor. It is likely that Eichmann, too, who did not have a permanent residence in Berlin and had arrived from Prague via Theresienstadt the day before, had stayed the night in the villa. This would certainly have made it easier for him to supervise the preparations on site in the morning.

After the “meeting followed by breakfast,” which started at noon and was probably officially over by 2 P.M., Heydrich, Müller and Eichmann stayed behind in the guest house—according to Eichmann—to relax over a glass of cognac and review the minutes of the meeting. The unnamed staff of the villa—quite possibly Jewish forced laborers, who looked after the house and gardens until February 1943—will have cleared up the conference room and washed the dishes in the meantime. Eichmann probably got straight to work on writing the Protocol, referring not only to his own notes but, by his own account, also to a transcript written by a—now unknown—shorthand typist. Heydrich flew straight back to Prague to host a reception in Prague Castle for the new government of the Protectorate at 7 P.M. the same day. There is no record of what the other participants did in the afternoon after the conference. The ministry officials probably drove back to Wilhelmstraße to continue working at their desks or to report to their superiors and staff on the outcome of the meeting. After work, perhaps they had a drink in one of the men’s clubs—the Nationalklub or the Aero Club—or in a bar on Friedrichstraße or Kurfürstendamm. What did they talk about with other guests or their families at home?

Read more in the Free Introduction to The Participants: The Men of the Wannsee Conference.

Residences of the Participants

1 Bühler: Krakow

2 Eichmann: Prague

3 Freisler: Habelschwerdter Allee 9/Hüttenweg 14 a, Zehlendorf

4 Heydrich: Brˇežany (near Prague)

5 Hofmann: Woyrschstraße 48, Tiergarten

6 Klopfer: Pullach (near Munich)

7 Kritzinger: Blücherstraße 6, Zehlendorf

8 Lange: Riga

9 Leibbrandt: Keithstraße 22, Tiergarten

10 Luther: Reichensteiner Weg 34–36, Zehlendorf

11 Meyer: Finkenstraße, Zehlendorf

12 Müller: Corneliusstraße 22, Steglitz

13 Neumann: Schwendener Straße 1, Zehlendorf

14 Schöngarth: Münster

15 Stuckart: Am Sandwerder 28, Zehlendorf