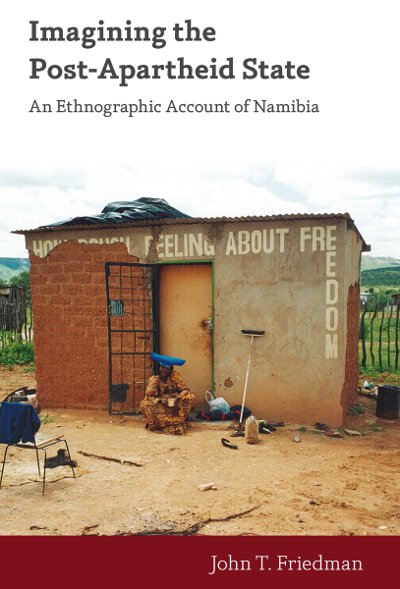

In 1990, Namibia gained its independence as a democratic state from the South African apartheid regime. Author John T. Friedman reflects on what this realistically meant and currently means for the making of a Namibian state in Imagining the Post-Apartheid State: An Ethnographic Account of Namibia, the paperback version of which was published last month after the original was published July 2011. Below the author explains his ethnographic method in an excerpt from the Introduction.

___________________________________

At first reading, the title of this book is likely to arouse some scepticism. How is it possible for an anthropologist to present an ethnographic account of Namibia, of an entire country? As anthropologists we are accustomed to investigate the localised, the small-scale, the village community. We are specifists, not generalists. The critic will thus be quick to suggest that any such attempt can yield only two possible outcomes: either a generalised account of ‘the Namibian people’, or a superficial survey of Namibia’s ethnic groups.

Of course, both approaches would result in essentialised and incomplete ethnographies. However, in proposing this ethnographic account of Namibia I am focused on neither the Namibian people, nor the Namibian peoples. Instead, in this book I aim to constitute the Namibian State itself as an ethnographic object of study. Here, I am nudging my way towards what Akhil Gupta and James Ferguson (1997a) have called an ethnography without the ethnos, or an ethnography beyond culture.

As such, this account takes ethnographic shape through its analytical positioning, its interpretive viewpoint and its holism; it is also ethnographic in its methodology, and in the sense that it aims to offer a ‘thick description’ (Geertz 1973) of its subject matter. In attempting to ethnographise the State, this work contributes to anthropology’s ongoing moves beyond the local in favour of those social formations and institutions altogether more complex, varied, global and dispersed. For this reason, it hopes to further de-centre the traditional anthropological gaze. Through such ‘location work’ (Gupta and Ferguson 1997b), then, this book aspires to help rethink ‘the field’ by exploring a methodological problem relating to the limits of ethnographic description. What might constitute an ethnography of the Namibian State, and how might an anthropologist study such an amorphous and problematic object?

At one and the same time, this book offers an empirical illustration of the Namibian State through the eyes and experiences of those that inhabit it. The case of post-apartheid Namibia offers a rich opportunity to explore such a bottom-up contribution to the study of state process. As Africa’s second youngest independent State, Namibia liberated itself from South Africa’s former apartheid regime in 1990. Today, the Namibian State and its inhabitants continue to negotiate their newfound democracy.

This ongoing process of state-making is contested at numerous levels. At the national level, political parties and their leading actors guide the State through a programme of post-apartheid reform. Among other issues, the crafting of Namibian unity and the transcending of the rural–urban divide remain high on the list of national priorities; all the while, we see neoliberal versions of the democratic state model intersecting with the SWAPO party’s attempts to retain control over what has become a dominant-party democracy. At the local level, however, we see quite a different set of parameters in the contestations surrounding the institutionalisation of the newly democratic State. In Kaokoland, a distant locale in the northwest part of the country, individuals and communities engage the new State in their everyday lives.

Here, the Namibian State is encountered as an educational system, a development project, a bureaucrat, a memory, a war wound and/or a patrilineal ancestor. It may be invoked, or avoided. Among Kaokolanders, the State is perceived as legitimate, corrupt, liberating, constraining, repressive and/or a new form of apartheid.

______________________________________

John T. Friedman is Associate Professor of Socio-cultural Anthropology at the University College Roosevelt of Utrecht University, The Netherlands. Before training as an anthropologist at Cambridge University, he worked in the field of international development. He has been researching and working in Namibia since 1993.