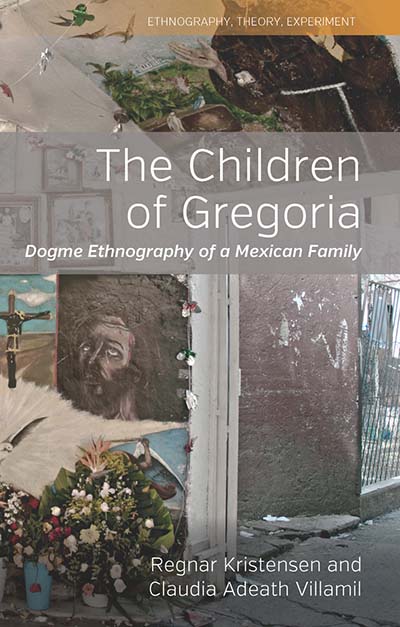

Dogme Ethnography of a Mexican Family

Now available, THE CHILDREN OF GREGORIA: DOGME ETHNOGRAPHY OF A MEXICAN FAMILY, by Regnar Kristensen and Claudia Adeath Villamil, is the latest volume in the ETHNOGRAPHY, THEORY, EXPERIMENT series. It portrays a struggling Mexico told through the story of the Rosales family. Regnar Kristensen expands on the authors’ process of dogme ethnography below.

Anthropologists collect during their fieldwork extensive, fascinating, and exciting stories. They transcribe large numbers of conversations and write lots of fieldnotes, however, most of this in-depth ethnographic material never gets published in an accessible, readable form for non-academics. Indeed, most monographs are written for other anthropologists or closely related scholars. They are evaluated according to academic conventions on reflexive- and theoretical depth, scholarly discussions, and cross-references.

This may very well be related to the academic professionalism, developed over decades, that accentuates the practice of assessing scholars more on their reflective and theoretical skill than on the extension and persuasiveness of their field material. Despite anthropologists constantly stating the importance of having a solid ethnographic basis, their anthropological knowledge is increasingly measured by the sharpness of their argument. A comment such as “it is a very rich ethnography” has, in Britain, turned into an ironic way of insinuating that a monograph is in fact chaos. But if we have lots of ethnographic recordings and transcriptions why not share them with a larger audience, also with those it is all about, and just for a little while put into the background our own participation and academic engagement?

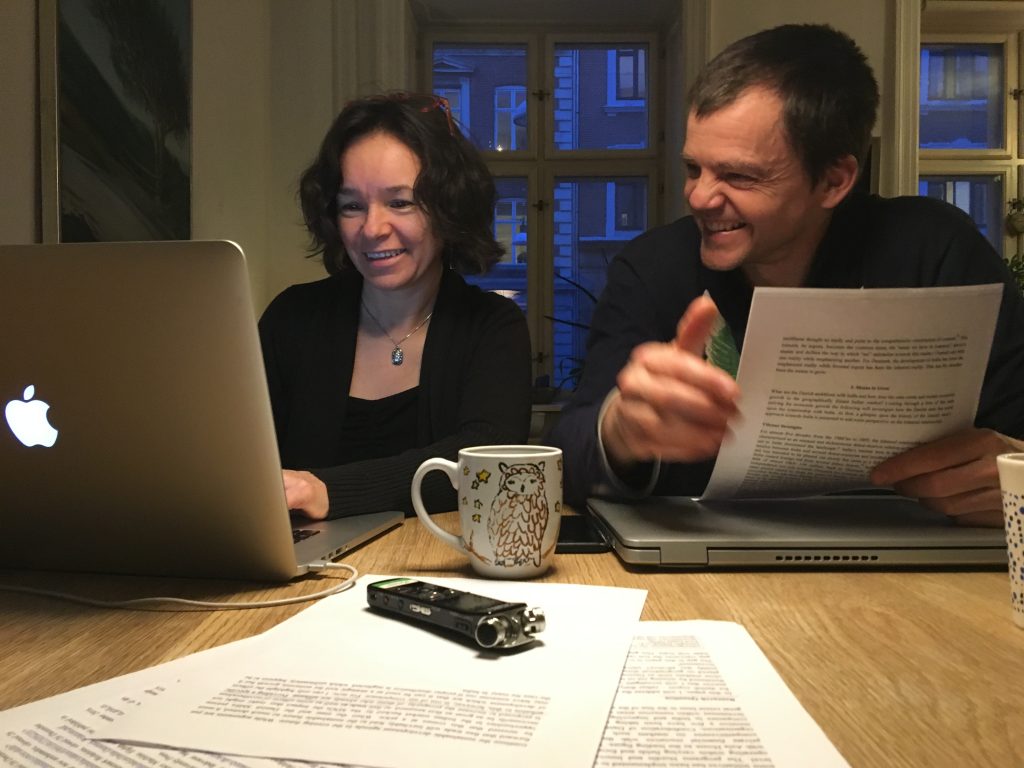

To contrast the tendency of favoring academic arguments and self-reflection over old school ethnographic description, I created ten dogme rules in 2012 to ensure that I and my co-author Claudia and our Cuban collaborator Yudy were engaged in a more descriptive way with our large number of transcribed pages and tacit knowledge of the cultural and social realities we studied. Claudia and I had followed a Mexican family for some years and wanted them to tell our readers their stories, which had captivated us so much. We recorded hundreds of hours of conversations with them, transcribed 3500 pages, and edited them into this book. Out came this odd literature that I call dogme ethnography (inspired by the Danish dogme 1995 film movement), but which could also be termed nonfiction-cinematic-memoir. This latter is due to its similarities with film production (the cutting and pasting of recorded tapes) and its narrative flow (a generational family story). It is not a novel, nor a traditional ethnography. Neither is it oral history, creative non-fiction, or memoir, but rather a mixture of all.

The dogme rules forced us into a more literary form of ethnographic writing in which the field site’s voices, so to speak, outshone the academic voiceovers. The two most important rules were that every word written had to be spoken into my or my wife Claudia’s microphone and that our own voices should be cut out in the published text. Based on these rules, other constraints were developed, the most far-reaching of which was an insistence on not inserting either arguments or descriptions into the text. Any analytical intent had to be communicated to the reader indirectly through meticulous editing and arranging of the family members’ voices.

We relied on both anthropological insight and literary techniques when cutting and pasting the transcribed stories, ordering them according to events, themes, or social relations, using flash backs, in media res, foreshadowing, and cliff hangers. We could not “see” the family members and their homes from above or “feel their fears,” much less invent things and details like in a novel to increase the suspense. Still, having several narrators, we had different distances and perspectives and were able to weave both some suspense and sociocultural themes into the master narrative by organizing the sentences, and the sequences, of their monologue. The result became a different monograph, easily read by non-scholars, spoken in the words of those studied.

I find it important to emphasize that the dogme rules were not shaped to diminish the importance of anthropological thinking and analysis. Rather than a critique of current practices, dogme-produced ethnography is a suggested way of diversifying the use and reach of anthropologists’ ethnography. If this dogme ethnography will reach a larger crowd is still to be seen. Berghahn decided to publish this English translation to scholars (with an added annex where I discuss the dogme method and the complications we came across). Simultaneously Grijalbo (Penguin Random House) decided to publish commercially the original Spanish version in Mexico. We look forward to following the reception of both and to seeing if it inspires to similar books and with time transform into other accessible products (e.g. podcasts, oral books, films). There are for sure thousands of ethnographic stories deserving to be published as the good stories they are. I believe much would be gained if those in-depth ethnographic stories could be published in a literary manner that drags more people into reading them; a prerequisite for appreciating the complicated lives and thoughts we encounter. The Children of Gregoria is our attempt.

THE CHILDREN OF GREGORIA

Dogme Ethnography of a Mexican Family

Regnar Kristensen and Claudia Adeath Villamil

Vol. 8, Ethnography, Theory, Experiment

Read Chapter 1, “The House in Ruins”

Regnar Kristensen is currently externally associated with the Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies of Copenhagen University. His fieldwork on the Santa Muerte cult has spanned many years, specializing in the interface between law enforcement, crime and religion in Mexico.

Claudia Adeath Villamil is a photographer and social art activist. She has lived most of her life in Mexico City, where her photo-documentary work has focused, amongst other things, on homeless women, street children, and the upsurge in the Santa Muerte cult.