This post is the transcript of an electronic interview between D. S. Farrer and Željko Jokić. Farrer is the special issue editor for Social Analysis Volume 58, Issue 1, and Jokić is the author of the article “Shamanic Battleground: Magic, Sorcery, and Warrior Shamanism in Venezuela” appearing in that issue. Below, Jokić answers a series of questions related to her article in Social Analysis.

This post is the transcript of an electronic interview between D. S. Farrer and Željko Jokić. Farrer is the special issue editor for Social Analysis Volume 58, Issue 1, and Jokić is the author of the article “Shamanic Battleground: Magic, Sorcery, and Warrior Shamanism in Venezuela” appearing in that issue. Below, Jokić answers a series of questions related to her article in Social Analysis.

This is the eighth in a series of interviews with contributors to this volume. Find the previous contributions on our blog.

What drew you to the study of War Magic & Warrior Religion?

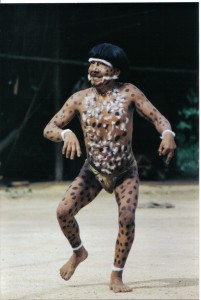

The main focus of my research is the nature of consciousness manifested in shamanism. While conducting fieldwork among the Yanomami people of the Venezuelan Upper Orinoco river region, I realised that the malevolent magical practices, assault sorcery, and destructive aspects of shamanism formed not only an omnipresent part of ethnographic reality but also an indispensable component of the Yanomami socio-cosmic system. This system is based on the governing principle of exchange of magical attacks and shamanic assaults between distant communities and is primarily motivated by revenge and retribution for past deaths.

With a few exceptions, the destructive aspect of shamanism has been largely neglected by researchers due to Western prejudices against violence and a discriminatory emphasis on the more positive, healing aspects of shamanism. As a result, malignant shamanistic practices were either misrepresented or intentionally omitted. More broadly, as a result of the recent upsurge of popular interest in shamanism among the Western urban middle classes, shamanism became a prominent spiritual approach to self-discovery in a trendy New Age fashion. In this newly emerging, entirely positive interpretation, shamanism is ‘rediscovered’ as a way of finding ‘our lost’ connections with nature, and provides a path of self-realisation, healing and empowerment. Within this framework, certain elements of shamanism, namely the positive aspects, are emphasised and selectively stripped of their cultural contexts, while other, more negative and destructive components are intentionally left out. To redress this imbalance, I decided to make assault sorcery a significant component in my research focus.

Did any perceptions on the subject change from the time you started your research/compiled the contributions to the time you completed the volume?

I approached my research on shamanism in terms of consciousness openly from the outset and managed to gain an insider’s perspective by becoming initiated into the practice. In time, I realised that the popular contemporary views on shamanism, especially outside of the narrow, specialist academic circles are entirely different from what I experienced while living among the Yanomami.

What aspect of researching and writing the chapter did you find most challenging? Most rewarding?

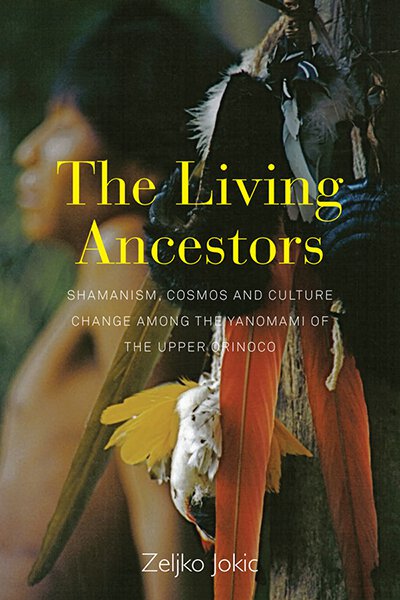

My chapter derives from the book The Living Ancestors: Shamanism, Cosmos and Cultural Change among the Yanomami of the Upper Orinoco, recently published by Berghahn. The most challenging thing for me was to choose case studies from the vast ethnographic material that I collected in the field. The most rewarding aspect of writing the chapter was the fact that my paper was the only contribution from South America in the entire volume.

To what extent do you think the book will contribute to debates among current and future academics within the field?

The book will most certainly contribute to debates among scholars and will serve as a reference point for many academics interested in magic and warfare. Considering the sensitivity of the topic and the ethical issues regarding the fieldwork, it may draw criticism from people who prefer to sweep these things under the carpet in their attempt to present cultures in more favourable light which in itself is a kind or reductionism that anthropology as a science tries to avoid.

Do you think there are aspects of this work that will be controversial to other scholars working in the field?

I think the very nature of the topic may seem controversial to scholars who prefer to view religion primarily as a peaceful endeavor.

If you weren’t an anthropologist, historian, what would you have done instead?

I would again be an anthropologist.

What’s a talent or hobby you have that your colleagues would be surprised to learn about?

I love cycling and bushwalking but that wouldn’t surprise any of my colleagues.

What inspired your love of the subject of War Magic? When?

It was basically an interest from the very young age that started with Edgar Rice Burrough’s books. During my adolescent years I got hold of Eliade’s monumental volume on shamanism and became fascinated by what I read albeit that it was very abstract for me and hard to comprehend at the time. During my undergraduate years at James Cook University, I read ethnographic texts dealing with shamanism and learned the fundamental principles of the ethnographic method. I was not quite happy with the principle of participant observation, thinking that in order to fully grasp the essence of shamanism and gain an insider’s perspective one has to become fully immersed into the practices. Consequently, full immersion became my primary method of ethnographic investigation, especially after I was initiated as a shaman. This of course became extremely dangerous for me considering the pervading harmful aspects of Yanomami shamanism.

What inspired you to research and write?

My research on shamanism became as much a personal quest for truth as well as a challenge to find an adequate theoretical framework and method for situating my ethnographic materials and presenting them in a literary form. I found the phenomenological method to be the most adequate vehicle for this purpose.

What is one particular area of interest or question, that hasn’t necessarily been the focus of much attention, which you feel is especially pertinent to your field today and in the future?

The main differences in terms of consciousness between traditional shamanism and the new forms of contemporary shamanism such as neo-shamanism or core shamanism as developed by Michael Harner.

What are the greatest challenges you have faced professionally, and how did you find it best to address them — as a writer, researcher, academic?

As a field researcher I faced many challenges in the hostile environment of the Amazonian rainforest. Perhaps one of the greatest challenges for me, especially in the beginning, was to adjust to the lack of privacy and adapt to full time living with the group. The greatest challenge as a writer was to place my ethnographic material into the appropriate theoretical context. An ongoing challenge for me as an academic is to gain a full-time University teaching position.

Zeljko Jokic is currently a Visiting Fellow at the School of Archaeology and Anthropology, Australian National University. Formerly, he worked as Research Assistant at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies and as Anthropologist Investigator at the Amazonian Centre for Investigation and Control of Tropical Diseases in Venezuela where he also worked as a Consultant for the Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the Americas.