A look into the life of post-Soviet Ukrainian women, Mapping Difference: The Many Faces of Women in Contemporary Ukraine is now available in paperback. This book uncovers the virtues of women that sometimes lie just beneath negative gender stereotypes. Following, editor of the collection, Marian Rubchak, gives readers a deeper look into the volume via the book’s cover.

A look into the life of post-Soviet Ukrainian women, Mapping Difference: The Many Faces of Women in Contemporary Ukraine is now available in paperback. This book uncovers the virtues of women that sometimes lie just beneath negative gender stereotypes. Following, editor of the collection, Marian Rubchak, gives readers a deeper look into the volume via the book’s cover.

_________________________________

Since the demise of the Soviet “Empire of Nations”[i] in 1991 Ukraine’s women have lived in a world largely shaped by the rejection of communist values and efforts to transform a moribund socialist system into an open democratic society. Early in the transformative period this society gave rise to a small core of female activists who chose to work within the existing system, with its traditional values, to effect the changes that would return their voice to women. Although they disavowed the label of feminist as a self-descriptor their agendas clearly reflected feminist principles.

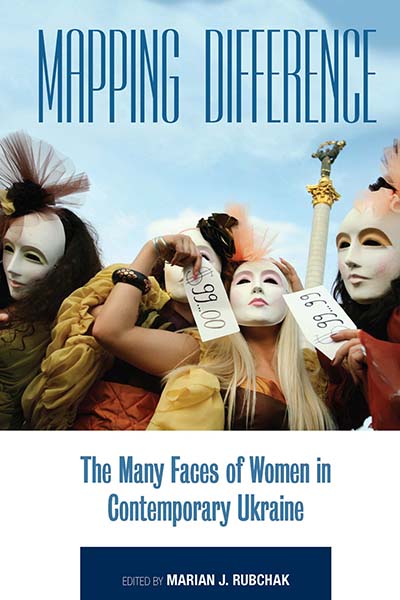

Sadly, however, in the newly created environment, filled as it was with so many exciting possibilities, women became the first casualties of attempts to direct Ukrainian society toward a market-driven economy. Their employment opportunities began to contract almost as soon as independence was declared. Two “career paths” became available as virtually the only major source of a living wage – massive outmigration to foreign shores to take up employment as migrant labor, and as workers in the sex industry. Sensationalism of the latter saturated the media, resulting in the widespread coverage that earned for the country a reputation of purveyor of cheap sex, as the cover image of Mapping Difference suggests. Conversely, the subtitle, The Many Faces of Women in Contemporary Ukraine ably dispels the notion of all Ukrainian women as suppliers of “sex for hire.”

The cover illustration was drawn from an internet posting in 2008 by a radical group of activists known as FEMEN.[ii] They announced as their primary objective the eradication of the evils of prostitution. Their protests were calculated to enlist maximum public support in raising awareness of the evils of prostitution, and eradicating (to the extent possible) Ukraine’s rapidly escalating sex industry. It showcases three women wearing kabuki masks and holding up signs advertising a charge of $99.00 for sexual services. Together with the title of the collection, the image creates a stunning paradigm of the word and image binary that describes the majority of Ukraine’s female population.[iii]

The kabuki references evoke three interesting paradoxes. The first and most obvious is the “image” of Ukraine’s women wearing masks, representing characterless uniformity, whereas the “many faces” in the subtitle – the ”word”— suggest the contrary concept, indicating variety. The second paradox is embodied in the same three figures,[iv] going against the title of Mapping Difference. The third paradox consists of men performing women’s roles. This resonates somewhat with the fact that contemporary men make decisions and pass laws for and concerning women, and reinforce them with negative stereotyping in the atmosphere of anti-woman discrimination that pervades Ukraine.

This juxtaposition of word and image allows us to look behind the kabuki masks, to view the diversity that describes the majority of Ukraine’s women. It enhances our appreciation of their efforts to cope with the realities of a harsh post-Soviet existence. It also suggests that Ukraine’s reputation as a prostitution paradise can be dispelled, as the collection’s context demonstrates. All of this enables us to acquire greater insights into the true reality of ordinary women’s lives, together with renewed sensitivity to the many challenges that Ukraine’s women face in their struggles to make a difference.

As Catherine Wanner explains in her Foreword to this collection: “Most notably, [the] authors illustrate … the enormous variety in understandings of gender and of gender-based problems, and how these understandings vary by region, profession, generation, and other social factors.”

Notwithstanding their modest numbers, members of the first generation of post-socialist women reformers began to display a feminist consciousness early into independence, but without tagging themselves as feminists. Their efforts to effect changes, seeking to bring them about within the existing context of societal values, laid a solid foundation upon which the next generation, the first truly post-Soviet generation unencumbered by values and demands transmitted from an authoritarian structure above might build a future with the potential for establishing a genuine “woman’s voice.”

Notes

[i] A description borrowed from the title of a book by Francine Hirsch, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005.

[ii] At the time of its formation in 2008 its primary focus was to combat prostitution. With time this agenda changed. See my “Seeing pink. Searching for gender justice through opposition in Ukraine,” European Journal of Women’s Studies (2012). Vol. 19, № 1.

[iii] Portrayed against a backdrop of Berehynia atop a towering pedestal — a traditional representation of female empowerment in the person of a mythical matriarchal goddess.

[iv] The kabuki configuration reflects a tradition that goes back to the beginning of the seventeenth century when women were trained to act on the stage on the one hand, and provide “special services” for men backstage. In the beginning, only women comprised the actors. By the middle of the seventeenth century, however, this arrangement had reversed itself and men became the sole players.

______________________________________

Marian J. Rubchak is Senior Research Professor, Valparaiso University, whose work focuses on reimagining Slavic identities in various contexts. She is the editor of Mapping Difference: The Many Faces of Women in Contemporary Ukraine (Berghahn 2011) and the forthcoming New Imaginaries: Youthful Reinvention of Ukraine’s Cultural Paradigm (Berghahn 2015).