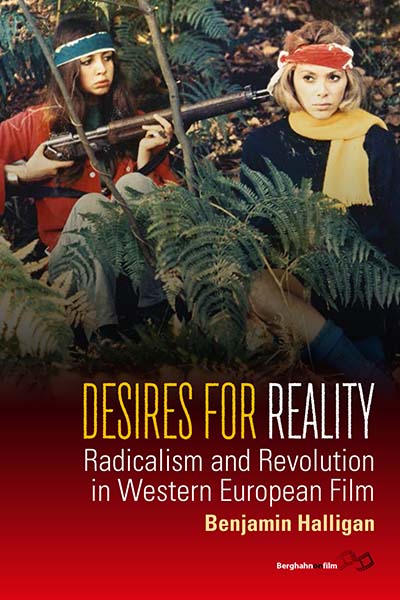

By Benjamin Halligan, author of DESIRES FOR REALITY: Radicalism and Revolution in Western European Film

My book Desires for Reality: Radicalism and Revolution in Western European Film was first published in 2016, and Berghahn Books just published a paperback edition.

Since the book concerns militant and radical film and film-making and the events of 1968, I very much wanted it to be out before 2018. My intention was that the book could contribute to the discussions that marked the 50th anniversary of 1968, and indeed it did. The ideal, in thinking about 1968, would not be commemoration and nostalgia but an engagement with the ideas of 1968 and their relevancy and challenge to today – that the collective desire to change our realities still, of course, remains, and film-making can still be considered in this context.

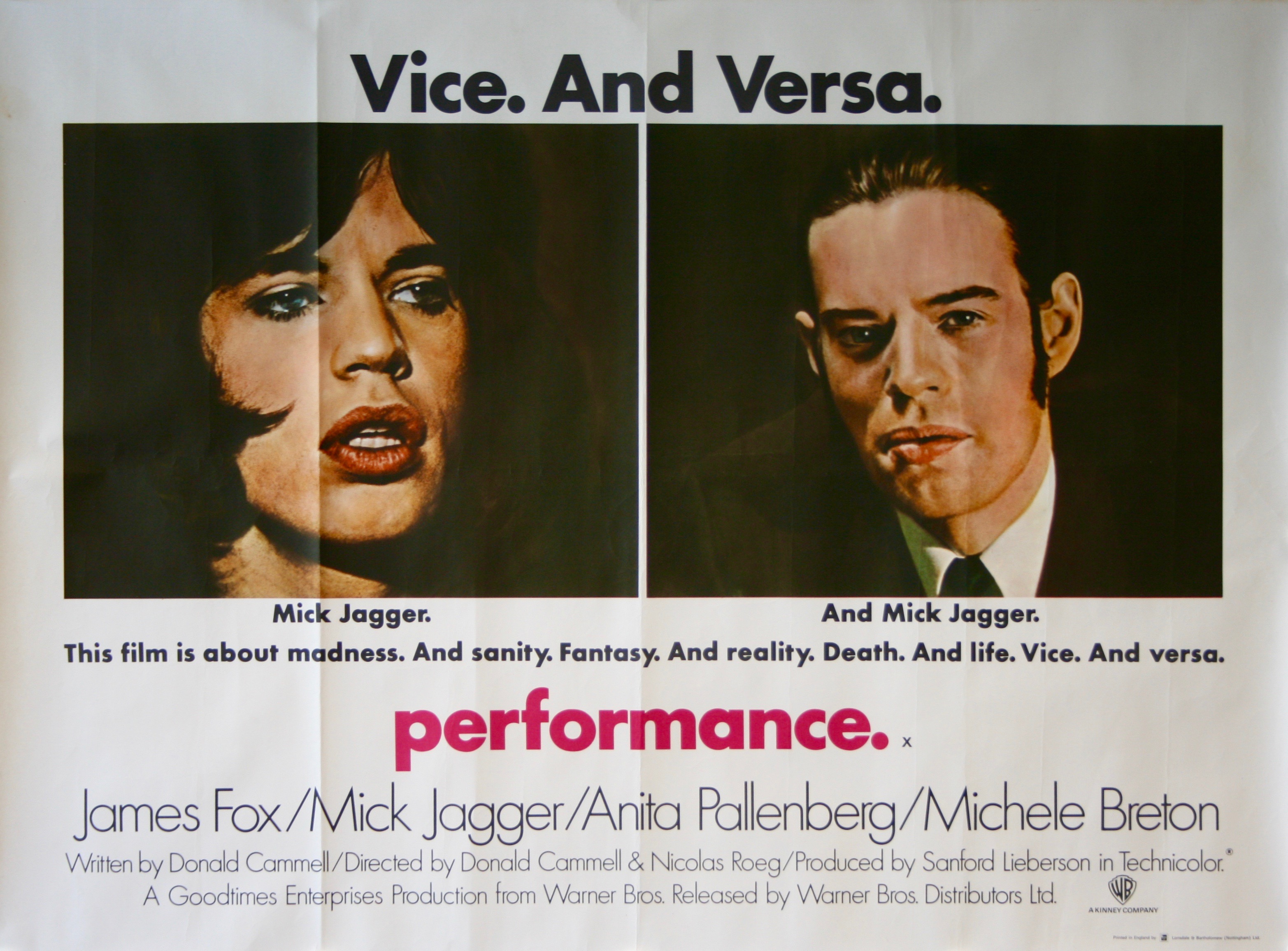

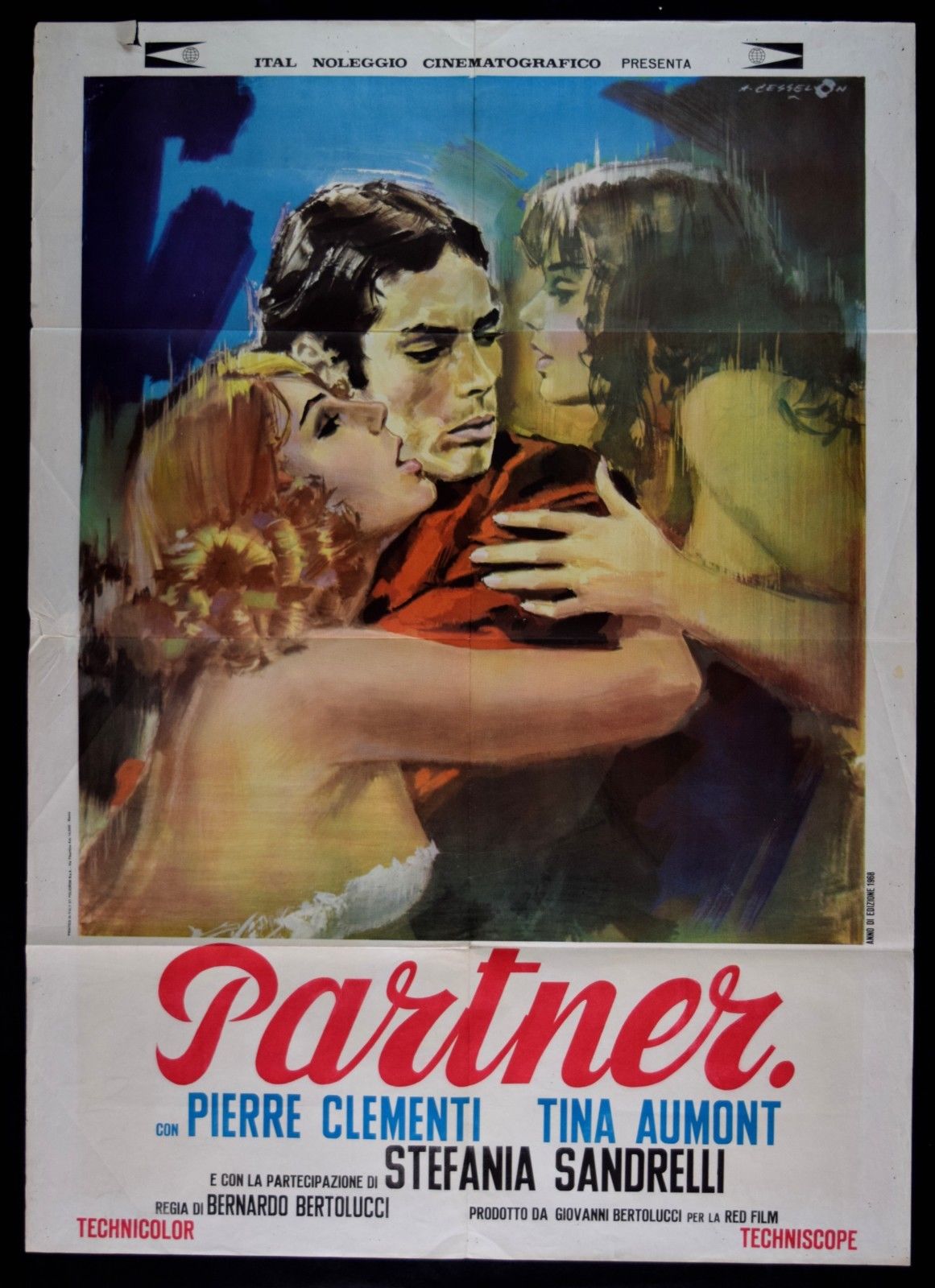

While the book deals with many of the now commonly accepted “classics” of that period, it also attempts to recover some still obscure films. In fact, it’s the existence of this divide – between the canonical and the Curate’s Eggs – that was a point of investigation. And, after the book was first published, the reactions to the November 2018 deaths of two film directors who featured heavily in it – Nic Roeg at 90 and Bernardo Bertolucci at 77 – further illustrated this sense of a divide. Their ’68 films are Performance (which Roeg co-directed by Donald Cammell) and Partner respectively.

The vintage of Performance seems to improve with every year: what other film offers an immersion in the rich bohemian ambience of the times? That musky Powis Square crash pad – messy four-poster beds, mushrooms in the greenhouse, communal baths, Persian rugs, a burnt-out rock star (Mick Jagger) experimenting with sonic happenings, and experimenting on a gangster in hiding – functions like a time capsule. To watch the film again is to step (back) into that world. I rewatched the film a couple of years ago at BFI Southbank, and a distinguished gentleman sitting directly behind me delivered most of the dialogue (complete with nuance and intonations) an anticipatory few seconds before we heard it on the soundtrack. Was Performance a talisman or ritual for him? I can’t doubt that it has loomed large in his life. And the enticement of the narrative ambiguities of Performance, its strange and Zeitgeisty undercurrents, and the mysterious intelligences that seems to organise its sounds and cuts so that it functions as psychedelic conceptual art, remain undiminished half a decade on. In Roeg’s obituaries, Performance was hailed as the high point of an artistic career that, at least until the early 1980s, was without parallel. It is arguably the most important post-war British film of the twentieth century.

Bertolucci’s Partner, on the other hand, remains obscure. This is doubly striking in a career that somehow held together international plaudits and popularity with aesthetic experimentation and an optimistic, lyrical Communism. Partner, I argue, seems to want to do more than cheer-on those manning the barricades in ’68 – it seems to attempt to weaponise Situationist impulses to inculcate a galvanising, revolutionary sensibility. Partner seems to be not about going to the cinema to understand societal matters, but going from the cinema to intervene in societal injustices. Tellingly, then, the film also contains a guide for Molotov cocktail-making. The critique is via Brecht; the ecstasy of revolution is via Artaud; the style is via Godard. The film is, of course, an impossible proposal. And it seems to have been addressed to a very specific audience – one that maybe only existed for a few months, or maybe didn’t exist at all. Partner barely figured in Bertolucci’s obituaries. And the film only really begins to make sense, I argue, in the context of the European cinema of 1968. If Performance is a live access to 1968, Partner is a dusty artefact of 1968.

Bertolucci’s Partner, on the other hand, remains obscure. This is doubly striking in a career that somehow held together international plaudits and popularity with aesthetic experimentation and an optimistic, lyrical Communism. Partner, I argue, seems to want to do more than cheer-on those manning the barricades in ’68 – it seems to attempt to weaponise Situationist impulses to inculcate a galvanising, revolutionary sensibility. Partner seems to be not about going to the cinema to understand societal matters, but going from the cinema to intervene in societal injustices. Tellingly, then, the film also contains a guide for Molotov cocktail-making. The critique is via Brecht; the ecstasy of revolution is via Artaud; the style is via Godard. The film is, of course, an impossible proposal. And it seems to have been addressed to a very specific audience – one that maybe only existed for a few months, or maybe didn’t exist at all. Partner barely figured in Bertolucci’s obituaries. And the film only really begins to make sense, I argue, in the context of the European cinema of 1968. If Performance is a live access to 1968, Partner is a dusty artefact of 1968.

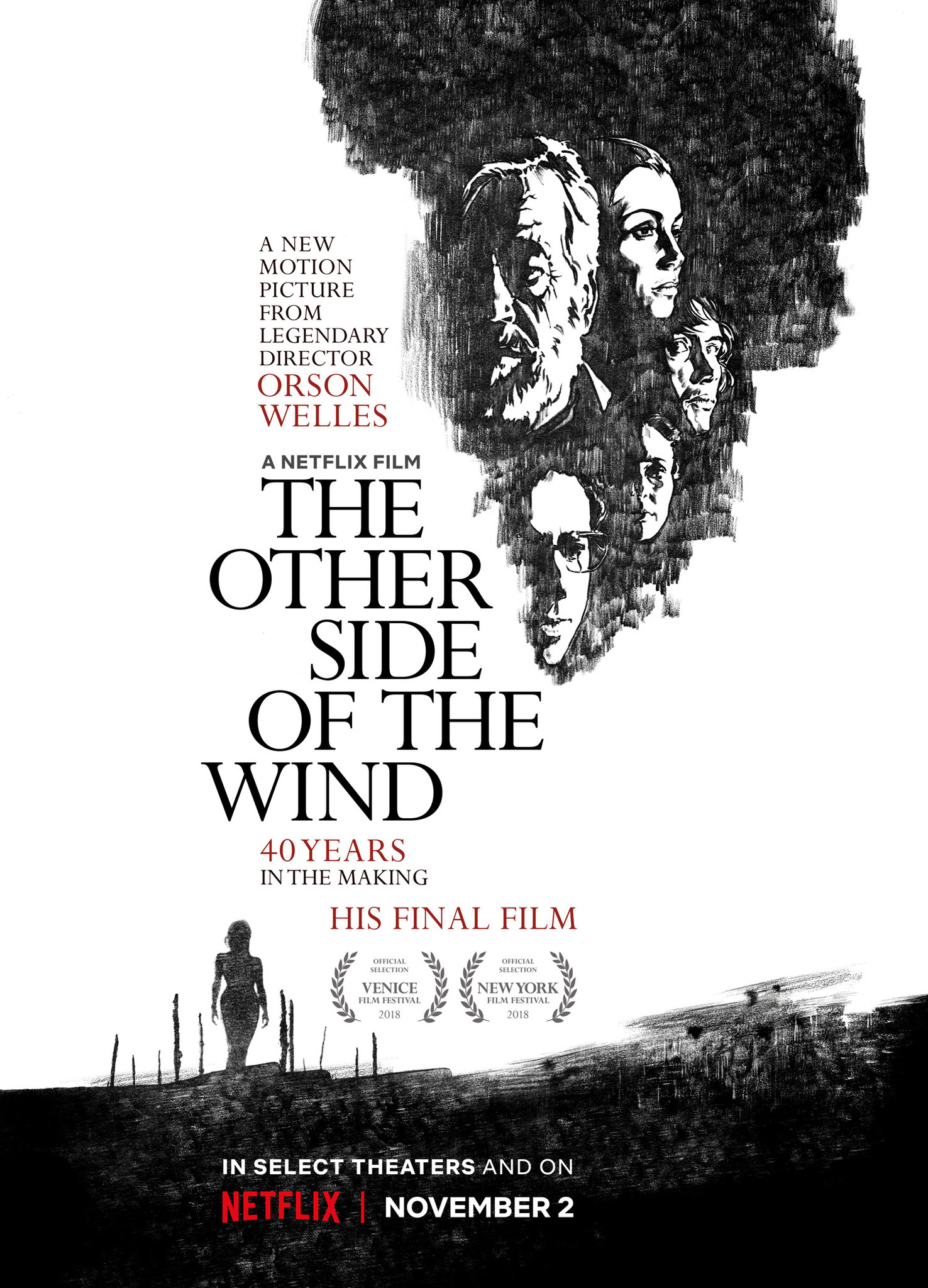

But a third 2018 “obituary” – an obituary, of sorts – suddenly appeared. This was in the release of Orson Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind – a film that was shot sporadically between 1970 and 1976, remained incomplete, and then became the stuff of myths and legends. The film cuts between two central narratives: a birthday party for an ageing film-maker, and extended sequences from a film that he has been shooting. These work-in-progress sequences seems to illustrate a careerist angling by the director to make a film a la 1968. Thus it is stylised to a high degree, pathbreakingly (for the time) sexually explicit, with a full embrace of the countercultural milieu, a film at times opaque and at times poetic, of long sequences of the type I discuss as “experiential”, and setting non-communicative hippies on the run across variety of deep-focus landscapes (as with Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point). Welles seems to be both pastiching and critiquing the cinema of 1968 – and the incomplete film-seen-within-this-film seems impossible: wildly idiosyncratic for the ageing film-maker who, at any rate (we learn at the start of The Other Side of the Wind), has died in, or committed suicide via, a car crash on the day of his birthday.

But a third 2018 “obituary” – an obituary, of sorts – suddenly appeared. This was in the release of Orson Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind – a film that was shot sporadically between 1970 and 1976, remained incomplete, and then became the stuff of myths and legends. The film cuts between two central narratives: a birthday party for an ageing film-maker, and extended sequences from a film that he has been shooting. These work-in-progress sequences seems to illustrate a careerist angling by the director to make a film a la 1968. Thus it is stylised to a high degree, pathbreakingly (for the time) sexually explicit, with a full embrace of the countercultural milieu, a film at times opaque and at times poetic, of long sequences of the type I discuss as “experiential”, and setting non-communicative hippies on the run across variety of deep-focus landscapes (as with Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point). Welles seems to be both pastiching and critiquing the cinema of 1968 – and the incomplete film-seen-within-this-film seems impossible: wildly idiosyncratic for the ageing film-maker who, at any rate (we learn at the start of The Other Side of the Wind), has died in, or committed suicide via, a car crash on the day of his birthday.

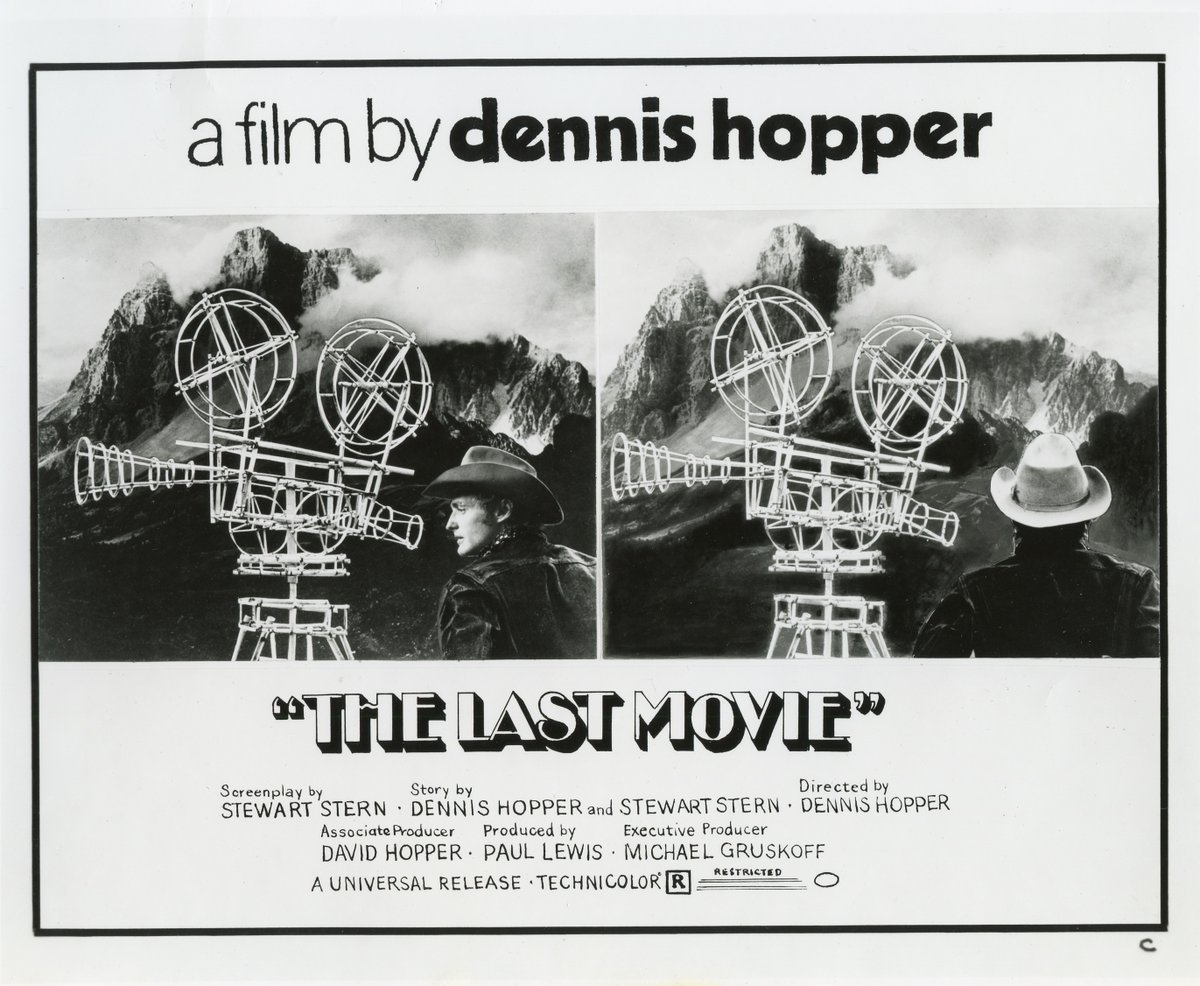

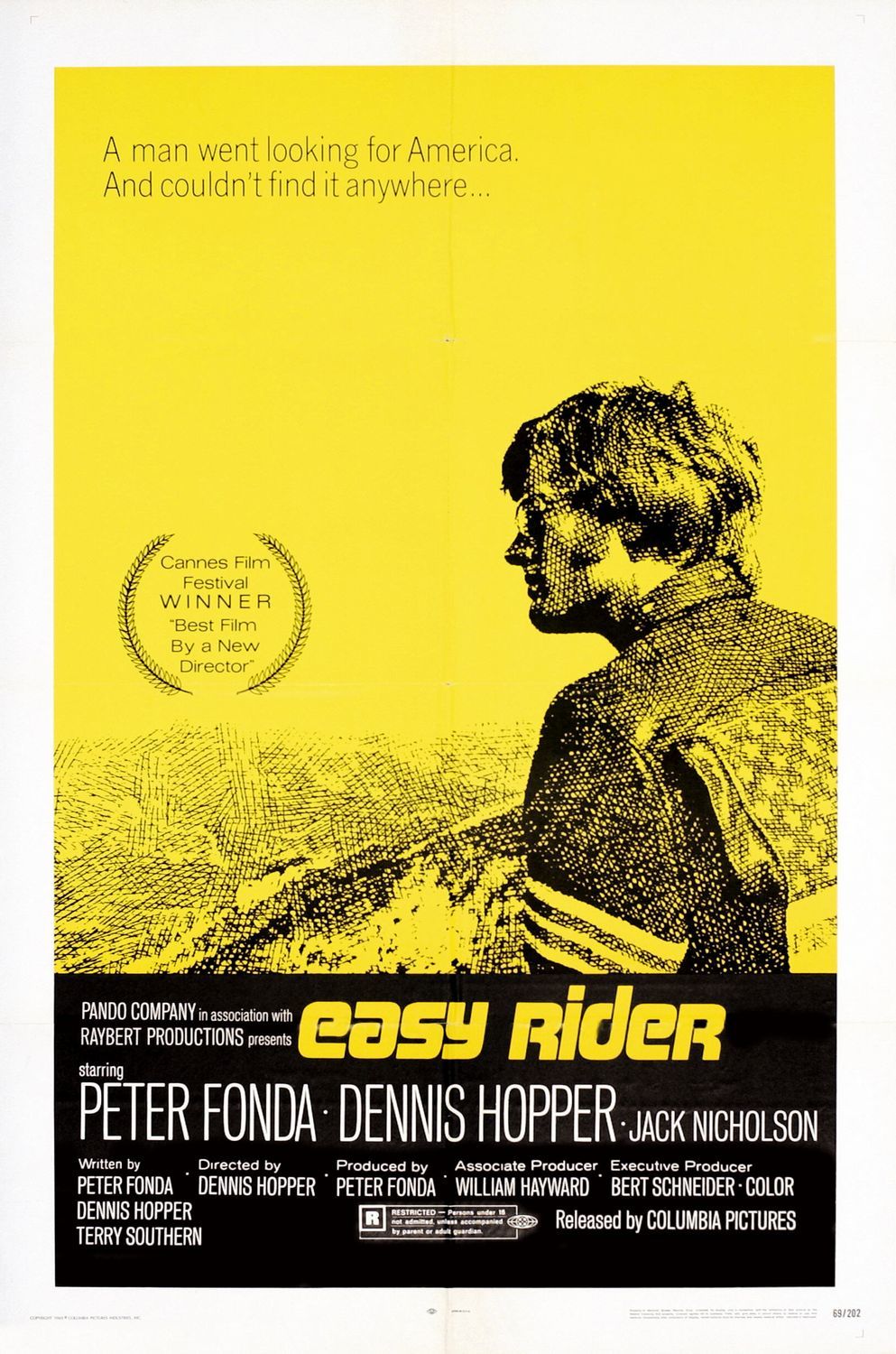

Welles’s position on the new cinema of 1968 seems ambiguous. On the one hand, the cinema of 1968 seems opportunist (the orgy sequence), tedious (self-important dialogue, aired at length), and even ridiculous (a woman chasing what looks like a giant phallus in the desert). In this sense, The Other Side of the Wind seems to offer an obituary of the cinema of 1968. But on the other hand the cinema of 1968 seems to be a giant step forward, and a remaking of the world. When the great Hollywood studio film-maker Douglas Sirk saw Easy Rider, he declared that his time was up, and ceased to make films altogether. The film-within-this-film resonates with the explosive synchronisation of the three revolutionary spheres of 1968: political, social, sexual. In this, in its hallucinatory, eroticised nature, Welles’s film even recalls pre-Doors Jim Morrison’s 1969 film HWY: An American Pastoral or Dennis Hopper’s post-Easy Rider film, The Last Movie (rereleased in 2018 after years of unavailability, and Hopper himself is glimpsed at the birthday party). The cinema of 1968, in its look and feel, and vibe and ambience, and intentions and desires, as The Other Side of the Wind seems to acknowledge, was like no other – and this even seems to have freed up Welles himself, as he entered his final phase of his career.

The last couple of years has also seen new films from two iconic New Wave and radical European film-makers, Agnès Varda and Jean-Luc Godard, who continue to mix (in the manner of 1968) the personal with the political, documentary with fiction, and remain, brilliantly and idiosyncratically, engaged with contemporary realities and issues. So 1968, from the vantage point of 2018, offered obituaries, a belatedly-received engagement, and altogether new films. I chose to open Desires for Reality with a blunt quotation from Alain Badiou, which I took to be a comment on the persistence of the paradigms of ideological struggle (and also spoke to the raison d’être for my book). But it is also a quote that now seems to function, thinking back, as an invigorating matter of fact: “We are still the contemporaries of May ’68.”

The last couple of years has also seen new films from two iconic New Wave and radical European film-makers, Agnès Varda and Jean-Luc Godard, who continue to mix (in the manner of 1968) the personal with the political, documentary with fiction, and remain, brilliantly and idiosyncratically, engaged with contemporary realities and issues. So 1968, from the vantage point of 2018, offered obituaries, a belatedly-received engagement, and altogether new films. I chose to open Desires for Reality with a blunt quotation from Alain Badiou, which I took to be a comment on the persistence of the paradigms of ideological struggle (and also spoke to the raison d’être for my book). But it is also a quote that now seems to function, thinking back, as an invigorating matter of fact: “We are still the contemporaries of May ’68.”

@benhalligan

www.benjaminhalligan.com

Benjamin Halligan is the Director of the Doctoral College of the University of Wolverhampton. His publications include Michael Reeves (2003), and the co-edited collections The Music Documentary: Acid Rock to Electropop (2013) and The Arena Concert: Music, Media and Mass Entertainment (2015).