This post is the transcript of an electronic interview between Philippe Willems and Berghahn blog editor Lorna Field. Philippe Willems is the author of the article Perspective Games: Cham’s Heritage and Legacy which appeared in European Comic Art, Volume 7, Number 1.

This post is the transcript of an electronic interview between Philippe Willems and Berghahn blog editor Lorna Field. Philippe Willems is the author of the article Perspective Games: Cham’s Heritage and Legacy which appeared in European Comic Art, Volume 7, Number 1.

What drew you to the archeology of the comic strip?

My relationship to the comic strip and its history is quite organic. Growing up in France, I learned to read before I entered grammar school by reading my parents’ Astérix books over and over again. At the time, there was a widespread consensus among educators that comics prevented children from reading correctly and even could impede their intellectual development. However, I ended up reading more grown-up books as a child than any of my friends. Is it a coincidence that, having become literate thanks to stories intimately blending words and images, I acquired a natural feeling for the narrative strategies they articulate? I think not.

Between the ages of 6 and 12 perhaps, every summer I would revisit stacks of 1960s issues of the magazine Spirou that stayed stored in boxes the rest of the year. I loved one of its regular sections, a history of the comic strip in installments by Morris and Pierre Vankeer entitled “Neuvième art. Musée de la bande dessinée” (ninth art. museum of the comic strip). It appeared without any chronological order, and its occasional incursions into 19th– and early 20th-century cartoons, so different from my familiar Franco-Belgian fare, fascinated me. At any rate, the 19th century was very much part of my natural environment. My grandmother lived in a seven-floor Haussmannian building now demolished. It had remained unchanged since the 1860s. The eerie central light/airshaft gave you a peek into the past if you dared look. There was a dark, quiet service staircase that tenants used less than the front one. Its combination of tiles, metal, and wood smoothed out by time gave you sensorial contact with the Second Empire, worlds away from the bustling street outside.

What about working with comic-strip history do you find most challenging? Most rewarding?

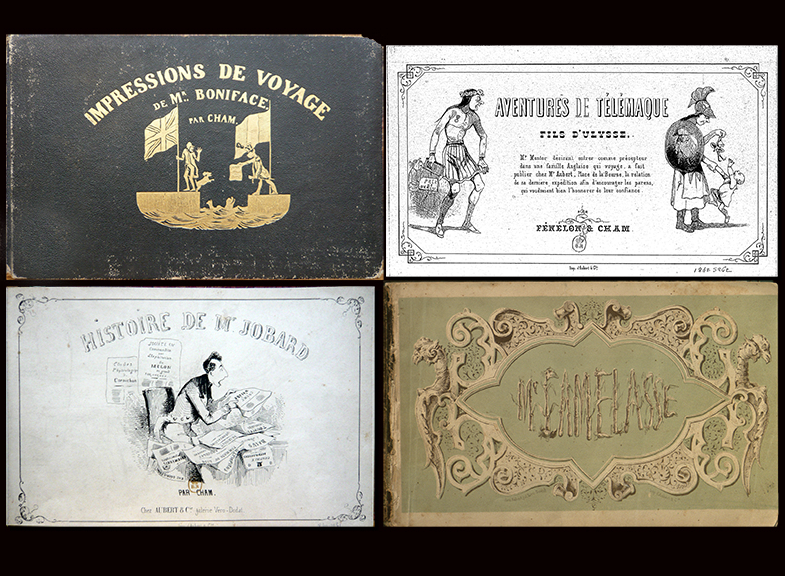

A challenging part of graphic-narrative archeology lies in locating primary materials. You need to collect a critical mass of documents before acquiring any meaningful overview of your subject. In the past few years, online collections have been making things vastly easier than when David Kunzle published his seminal, encyclopedic History of the Comic Strip. However—and fortunately for the rest of us—there still is digging to do, and I love going to libraries, handling rare, sometimes mythical, books, and searching through entire collections of antique periodicals page by page, wondering who has turned them before.

I find it rewarding to feel that I am contributing new elements to our knowledge of how meaning is constructed when words and images combine. I was inspired to get into this line of work by the research of scholars such as Kunzle, Thierry Groensteen and Thierry Smolderen, and it feels good to add my brick to their edifices. As far as this specific article on Cham is concerned, I take pride in unearthing the roots of jokes so classic that we had lost trace of their origins. Overall, I find it funny that a narrative form condemned by so many of my teachers defines my academic work today. That’s quite a reversal. My research interests, however, are not limited to the comic strip (see http://philippewillems.wordpress.com).

You underline a paradox at the core of your relationship to your field of study. Is there anything else in your professional life that you find paradoxical?

My son is almost three years old. As he grows up, the shelves where I keep hard-cover graphic novels and bound periodicals that have survived the assaults of time across decades, and centuries, for some, will dangerously get within closer and closer reach. I can already see myself saying something like “You know, these are daddy’s comic books. They are fragile. You can play with them when you’re 20 or 30.”

CLICK HERE TO READ PHILIPPE WILLEM’S ARTICLE IN EUROPEAN COMIC ART. TO GET A FREE 60-DAY ONLINE TRIAL OF THE JOURNAL, CLICK HERE.