By Richard O’Connor, author of From Virtue to Vice

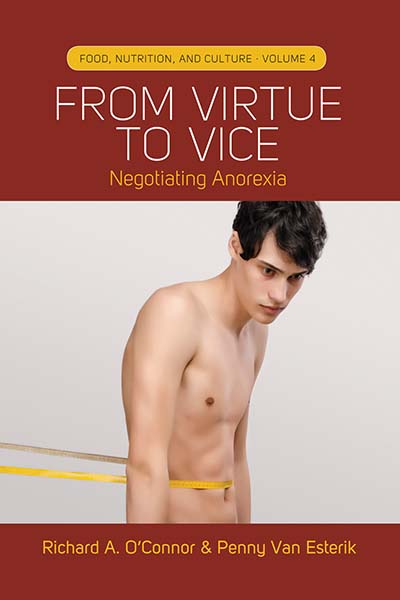

Richard O’Connor, professor of anthropology at the University of the South, is the author of From Virtue to Vice: Negotiating Anorexia. His book, written with Penny van Esterik, is Volume 4 in our Food, Nutrition and Culture Series that takes an anthropological perspective to human nutrition and food habits. In this blog post, Professor O’Connor debunks five commonly held beliefs on the disease that benefits clinicians, patients, and the friends and family of those who struggle with anorexia.

Richard O’Connor, professor of anthropology at the University of the South, is the author of From Virtue to Vice: Negotiating Anorexia. His book, written with Penny van Esterik, is Volume 4 in our Food, Nutrition and Culture Series that takes an anthropological perspective to human nutrition and food habits. In this blog post, Professor O’Connor debunks five commonly held beliefs on the disease that benefits clinicians, patients, and the friends and family of those who struggle with anorexia.

Myth: Anorexia is a woman’s disease. No, men get exactly the same syndrome by exactly the same practices. It’s all about discipline, not gender. With eating or exercise, by disciplining yourself strictly, men as well as women can make body-wracking training and starving into tenacious habits. Why then does anorexia strike more women than men? Gateway practices like weight-loss dieting and super-healthy eating involve women more than men. Yet other gateways, like training intensely for sports or dance, are gender-neutral. Although many say only one anorexic in ten is male, those statistics are flawed. Most anorexia slips below the radar. When the Mayo Clinic went deeper, combing Rochester, Minnesota’s health records over fifty years, researchers discovered health statistics missed most cases. So you cannot just count sufferers who come to the clinic and get diagnosed correctly. To get accurate data, you must go out into the community and see what’s there. By that procedure the Ontario Home Health Survey found one anorexic in three was male.

Myth: People with anorexia diet for beauty. No, what drives the disease is achieving, not appearance. It starts in how ambitious and well-organized people set, meet and then raise their goals. When that goal is physical self-improvement (improving at dance or a sport; losing weight; eating healthy), top achievers sweat the details so intensely that the day-to-day means (restricted eating; relentless exercise) become ends in themselves. Then the setting/meeting/raising loop tightens into a trap. Suddenly, to feel good about yourself, you keep raising the bar. Soon your social life shrinks into your regimen. You push away friends and family. Eventually your body becomes haggard—you get dark circles under hollow eyes; a shrunken body makes your head look huge; head hair falls out; a downy fuzz grows on shriveled limbs. Some flaunt the change while others hide it with makeup and baggy clothes, but sooner or later everyone looks deathly. How ironic then that popular thought supposes these hardened achievers are frivolous girls starving to be supermodels!

Myth: Anorexia reveals some dark trauma or deep failing. No, all anorexia reveals is how habit and training can hijack a life. Like Olympians, willful people train themselves into extreme self-denial. What begins as self-improvement thereby morphs into self-destruction. That reversal blindsides its victims. They cannot explain how their controlling goes out of control, how their regimen takes on an overpowering life of its own. Now trapped in a deadly disease, everyone assumes it must have a hugely compelling cause. Yet no one has found this deeper evil, not even after over a century of trying. Why? There is little or nothing to find. Our study uncovered mostly trivial reasons: youthful curiosity (‘How far can I go?’), overconfident achieving (‘I have the will to do whatever I want!’), adolescent angst (‘My life feels out of control!’). That is not to deny that some who suffer anorexia do have deep pathologies. It simply says that the disease that everyone gets— the common denominator—is nothing deeper or darker than training taken too far. Many, perhaps most, cases are accidents, not inevitabilities.

Myth: People with anorexia could get well if they wanted to. No, the disease eats away free will from inside and out. The outside is easier to track. To keep their strict eating and exercise rules, these achievers must avoid friends and family or fool them altogether. Their rule-keeping thereby isolates them mentally and often physically from normal social life. Meanwhile their inner life of rule-making and goal-reaching grows richer and more engaging. That starts slowly—adding a rule here, tightening self-enforcement there—until suddenly the bits and pieces crystalize into an all-or-none lifestyle. Then giving in anywhere feels contemptible (‘Eating that is disgusting!’), even dangerous (‘I’ll fall apart!’); comfort eating and ease once gave shifts to confidence in their ritualized practice (‘I can rely on my eating disorder.’); and some adopt an anorexic identity that traps them further. Deadly as these inner changes are, it is neither odd nor abnormal to rearrange oneself. All of us have differing sides that change as we grow and move about. In this dynamic anorexics-to-be just give their rule-making side a greater and greater say until it pushes out or shouts down the person’s other facets. How does the whole person return? Sometimes therapy rescues them. Other times courageous sufferers reverse direction, baby-stepping out of the syndrome the way they got in. Either way, friends and family who want the whole person back—who refuse to give up or be shouted down—act as a lifeline.

Myth: People with anorexia cannot see how thin they are. No, most anorexics not only know how thin they are, they take pride in how their body proves their willpower. The idea that they cannot literally perceive their shrunken bodily state—that they have a distorted body image—originated with Hilda Bruch and caught on in the 1960s. It is still listed as a symptom but by the 1990s it was scientifically discredited as integral to anorexia. How did this myth get going? One explanation is that Bruch was a pushy therapist whose patients pushed back by defending their thinness. Seeing this denial as unrealistic, Bruch supposed it anchored the pathology. What she did not realize, however, is that most people today have unrealistic bodily attitudes. Indeed, to live a modern and progressive life, you criticize your bodily failings and unhealthy habits, all the while making plans to do better. Of course most plans fizzle. What sets anorexics apart is that they act on their plans and get results.

Richard A. O’Connor is Biehl Professor of International Studies and Anthropology at The University of the South. He has held postdoctoral awards nationally (Fulbright, SSRC-ACLS, NEH) and abroad (Kyoto University and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies).