In January 2012, a white man was cast for the part of an African American man in “I’m Not Rappaport” for the German adaptation of the U.S. play. The plan to use blackface makeup—common in American theater up until the Civil Rights movement—to change the man’s appearance stirred controversy, and was called out as racist. Co-editor of Germany and the Black Diaspora: Points of Contact, 1250-1914, Martin Klimke addresses the sensitive subject of race in Germany in light of this event.

_________________________________________

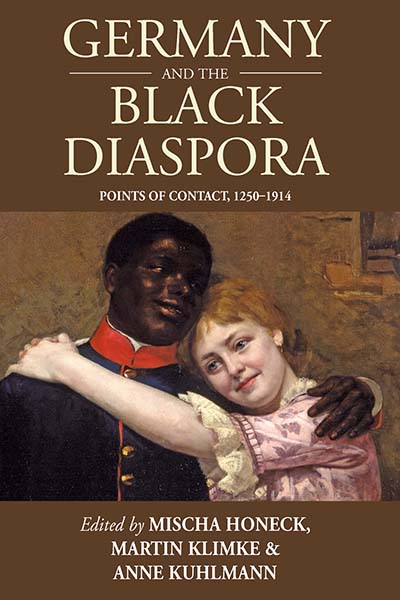

Germany’s place in the Black Atlantic might have been peripheral in a geographical sense. Intellectually and discursively, however, it played an often underestimated but significant role in the formation of modern social, racial, and national identities.

This is not to say that German nationhood would not have taken shape without the contributions of people of African descent. However, in light of the findings presented in this volume, accounts of German nation-making that conceal or ignore black agency are no longer acceptable. Even today, as Germans cautiously move toward accepting the reality of living in a multicultural society, anti-black racism remains a touchy and uncomfortable subject. Unaware of the racist legacy of American minstrel shows, a popular Berlin theater ensemble had a white actor play a role in blackface in January 2012. The directors were stunned that this move unleashed a torrent of criticism and passionate exchanges on various blogs and online forums. Likewise, the decision of the investigative reporter Günter Wallraff to go undercover as a black man to expose racist behavior in contemporary Germany was probably well-intentioned but backfired when Afro-Germans faulted him for what they regarded as ill-informed and patronizing conduct. No less disturbing is the survival of street names in Berlin such as “Togostraße” and “Lüderitzstraße,” both allusions to German colonial rule and exploitation in Africa. To this day, city authorities have done nothing to change the names or at least furnish the street signs with explanatory captions. Many more examples could be added to this list. But these should suffice to show that the tendency to treat blacks in German history and culture as perpetual strangers and as the immutable “other,” in a very palpable sense, lasts into our time. True, historians of Germany and Germans themselves have started to confront the country’s colonial and imperial legacies. Yet in light of recent Neo-Nazi outrages and concerns about no-go areas for darker-skinned people cropping up all over Europe, many more steps are needed to arrive at a more tolerant and inclusive concept of community. This volume thus seeks to raise awareness about a long, though oftentimes still neglected, tradition of black presences in German society that has had and continues to have a place in the nation’s sociopolitical fabric. ___________________________________________