by Ulrich E. Bach

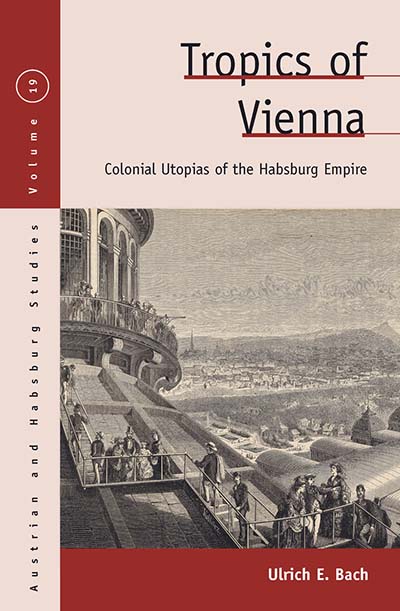

From the digital perspective of today, visual media reproduced in 19th century publications often appear quaint if not antiquated. To be sure, daguerreotypes and photographs could already capture cityscapes, but due to technological limitations, these reproductions were too static and timeless in order to represent contemporary life in newspapers. The busy everyday life in the contemporary metropolis was better captured in graphic illustrations, which were printed and distributed in huge quantities. For this reason, I chose Franz Kollarz’ xylograph “Auf dem Dach der Rotunde” (1873) as the book cover of Tropics of Vienna: Colonial Utopias of the Habsburg Empire. For me, the optimistic World Exhibition visitors—gazing like explorers—encapsulate not only the optimistic spirit of the time, but also give a glimpse into the general societal aspirations of the Habsburg Empire.

From the digital perspective of today, visual media reproduced in 19th century publications often appear quaint if not antiquated. To be sure, daguerreotypes and photographs could already capture cityscapes, but due to technological limitations, these reproductions were too static and timeless in order to represent contemporary life in newspapers. The busy everyday life in the contemporary metropolis was better captured in graphic illustrations, which were printed and distributed in huge quantities. For this reason, I chose Franz Kollarz’ xylograph “Auf dem Dach der Rotunde” (1873) as the book cover of Tropics of Vienna: Colonial Utopias of the Habsburg Empire. For me, the optimistic World Exhibition visitors—gazing like explorers—encapsulate not only the optimistic spirit of the time, but also give a glimpse into the general societal aspirations of the Habsburg Empire.

As the capital of a vast empire, Vienna took civic pride in hosting the 5th World Exhibition in 1873. The spectacle showcased more than 25,000 exhibitors, and accommodated 7,000,000 visitors from around the globe. Tellingly, the city experienced an unforeseen period of growth when its population was increasing from around 600,000 in 1869 to almost two million in 1910. Due to concurrent improvements in the railway system, technical innovations in a swathe of coal-consuming industries, and the ever-expanding financial sector, (social) mobility intensified in the Habsburg monarchy.

Utopian narratives can be seen as symbolic solutions to unconsciously felt contemporary communal problems. Hence, the task of critics is to find the means of reconstructing the underlying history for which the text as symbolic act serves as a solution. If one applies Frederic Jameson’s concept of the political unconsciousness, which postulates an implicit political dimension of creative works of art to the utopian novels discussed in Tropics of Vienna, one will find that—for instance—liberal economist Theodor Hertzka’s society portrayed in Freiland (chapter 3) is not merely futuristic, but it is rather a reformed community founded on the positive aspects of liberalism before the Gründerkrise in 1873. In other words, Hertzka harks back in his utopia to the spirit of the enlightenment, where the freedom of the individual is paired with steady evolvement of the individual. As we can see in his novel Freiland, when Vienna’s prosperity of the late 1860s came to a shrieking halt with the stock market crash in May 1873, Hertzka’s reevaluated his erstwhile confidence in unfettered liberalism and his belief in the perennial technological progress. Instead of inventing futuristic economic concepts, he rather sought to realize models of the past. A couple of years earlier, another economist, Karl Marx, ingeniously captured the value of the past in a letter to the philosopher Arnold Runge: “Lastly, it will become evident that mankind is not beginning a new work, but is consciously carrying into effect its old work.”

Ulrich E. Bach is a Visiting Associate Professor of German at Wesleyan University, Connecticut. His research focuses on late 19th and early 20th century cultural studies. His work has appeared in publications such as German Quarterly, Utopian Studies, and Film & History. Berghahn Books, New York recently published his monograph Tropics of Vienna: Colonial Utopias of the Habsburg Empire.